Mention beaks and typically we think of birds. Balloons make us imagine parties and predators are large beasts with sharp teeth. But one group of flies, the Empidoidea or dance flies, relates to all three: beaks, balloons and predators. And that is only the beginning of their intriguing looks and lives!

Empidoidea are found all around the world and there are estimated to be more than 7,500 species, about half of which have been described to date. Aotearoa New Zealand is a hotspot of diversity for the group.

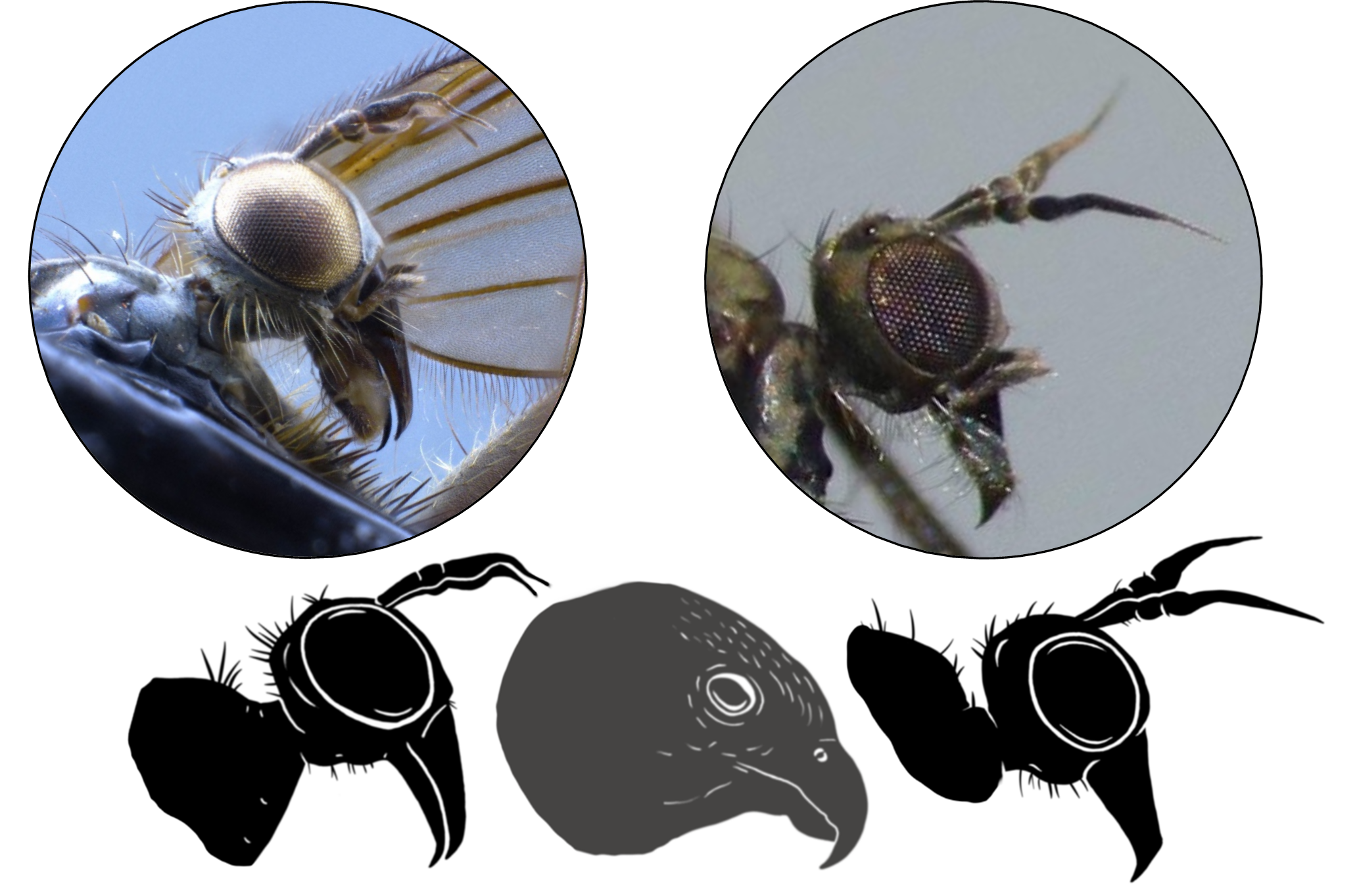

Most of these flies are voracious predators, hunting and catching prey on the wing. Many have large grasping forelegs covered in spines and dagger-like mouthparts which they use to stab their prey – a deadly combination. Although the majority of the dance flies are predators, some use their long dagger-like mouthparts to feed on nectar from flowers instead.

A group of dance flies called the Hemerodomiinae take long grasping forelegs to the extreme. With their sharp spines, these flies' forelegs are like those of a praying mantis! They are typically found on rocks and vegetation around the edges of streams and rivers, and many species' larvae live in these waterways before they mature into adult flies.

The Empidoidea are often referred to as dance flies because of dance-like flight patterns in the swarms some species form when trying to find a suitable mate. Many species in the group use nuptial gifts to woo potential mates, or at least to distract them while they mate. Typically males, although in some species it is the females, catch a tasty prey item to present to a potential partner before attempting to mate with them.

The Hilarini, commonly called balloon flies, are a subgroup of the dance flies. These species make additional efforts when it comes to nuptial gifts. It turns out it isn’t only spiders which spin silk; these flies have a swollen foreleg segment containing a silk gland which they use to neatly gift wrap their prey as a balloon before presenting it to a potential partner. However, these crafty flies sometimes resort to trickery. Instead of wrapping something desirable, some flies wrap up bits of prey that they have already eaten themselves or inedible pieces of plant material.

Although dagger-like mouthparts are common amongst the dance flies, one group from the genus Hydropeza have beak-like mouthparts. Just like the sharp, curved beaks of birds of prey, these mouthparts are effective for hunting prey. Hydropeza flies are notoriously tricky to catch because they spend their time skimming rapidly over the surface of streams, pools and cascades or waterfalls. In fact, they were given their name to highlight just that: Hydro means water and peza means foot.

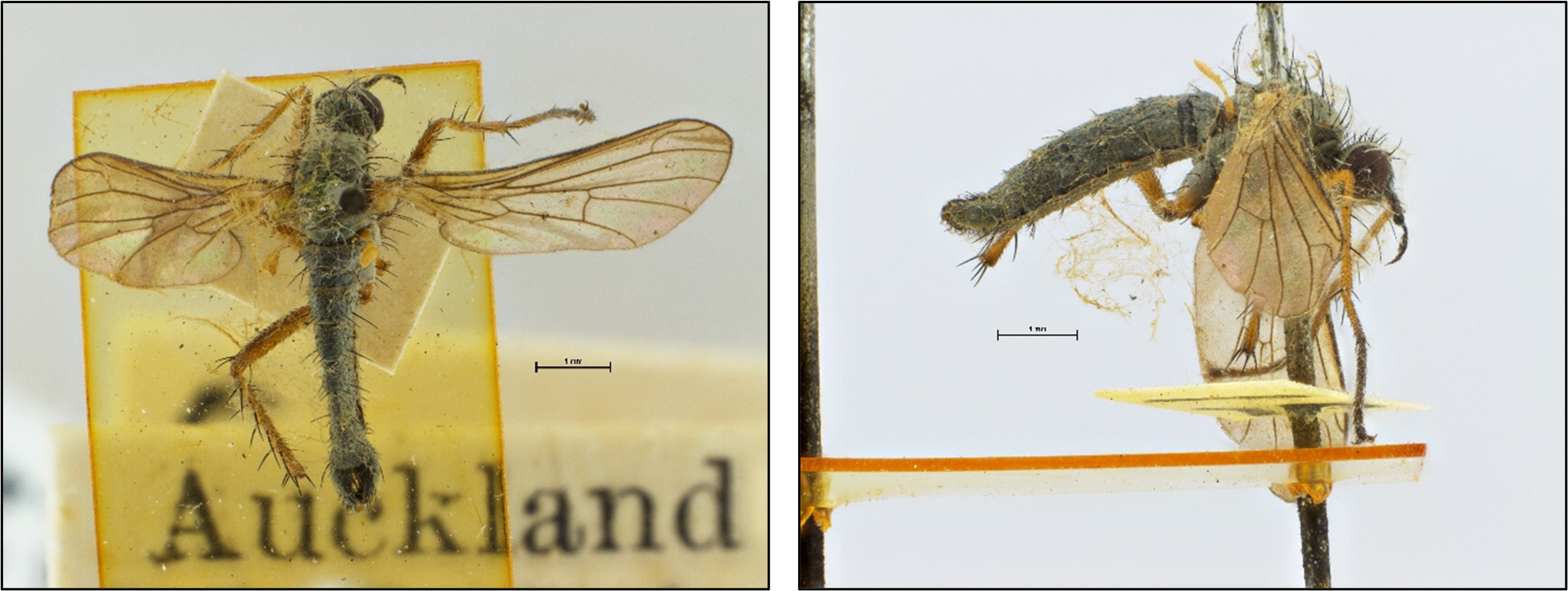

Recently scientist Steve Kerr, who works on flies at Otago Museum, was interested in taking a closer look at Canterbury Museum’s oldest Empidid specimen. This fly was collected from the Auckland Islands in 1907 on the Canterbury Philosophical Institute Sub-Antarctic Expedition. At the time these specimens were identified by George V Hudson, one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s most renowned entomologists (insect scientists), who published his first book on entomology in 1892 at the age of 19.

Unfortunately, in this instance Hudson wrongly identified the species. But now, more than 100 years later they have finally been correctly identified as a species of Empidadelpha, providing the first record of this species on Auckland Island, adding a new piece of information to our understanding of the biodiversity of our sub-Antarctic islands.

If one group of flies such as the Empidoidea can harbour this much diversity and intrigue, imagine what amazing things are happening across the other approximately 160,000 Diptera (fly) species known in the world!