Sharks are predators of the ocean, but some snails are just as deadly predators of the forest.

But, just like sharks threatened by overfishing, Aotearoa New Zealand's carnivorous snails are endangered by human activity.

These beautiful killers mainly eat earthworms, along with many other inverterbrates like small insects and even other snails. The snail moves surprisingly fast to grab prey with its mouth. It then sucks the earthworm into its mouth like grisly spaghetti, where it is enveloped and suffocated. Once dead, the worm is torn apart by the snail’s sharp, rasping teeth. These teeth, known as radulae, sit in a deadly ribbon in the snail's mouth. Carnivorous snails in the Southern Hemisphere belong to the family Rhytididae and are found throughout the Pacific, Australia, southern Africa, and Aotearoa New Zealand. There are several different kinds of carnivorous snail in New Zealand, including the large and rare Paryphanta (kauri snails) and Powelliphanta snails. Smaller ones like the Wainuia, which is named after the Lower Hutt suburb of Wainuiomata, catch and eat land hoppers.

All snails have radulae, not just the carnivores. The common garden snail has over 14,000 radulae which it uses to eat plants. Other snails, which are known as detritivores, use their radulae to break down decaying plant matter.

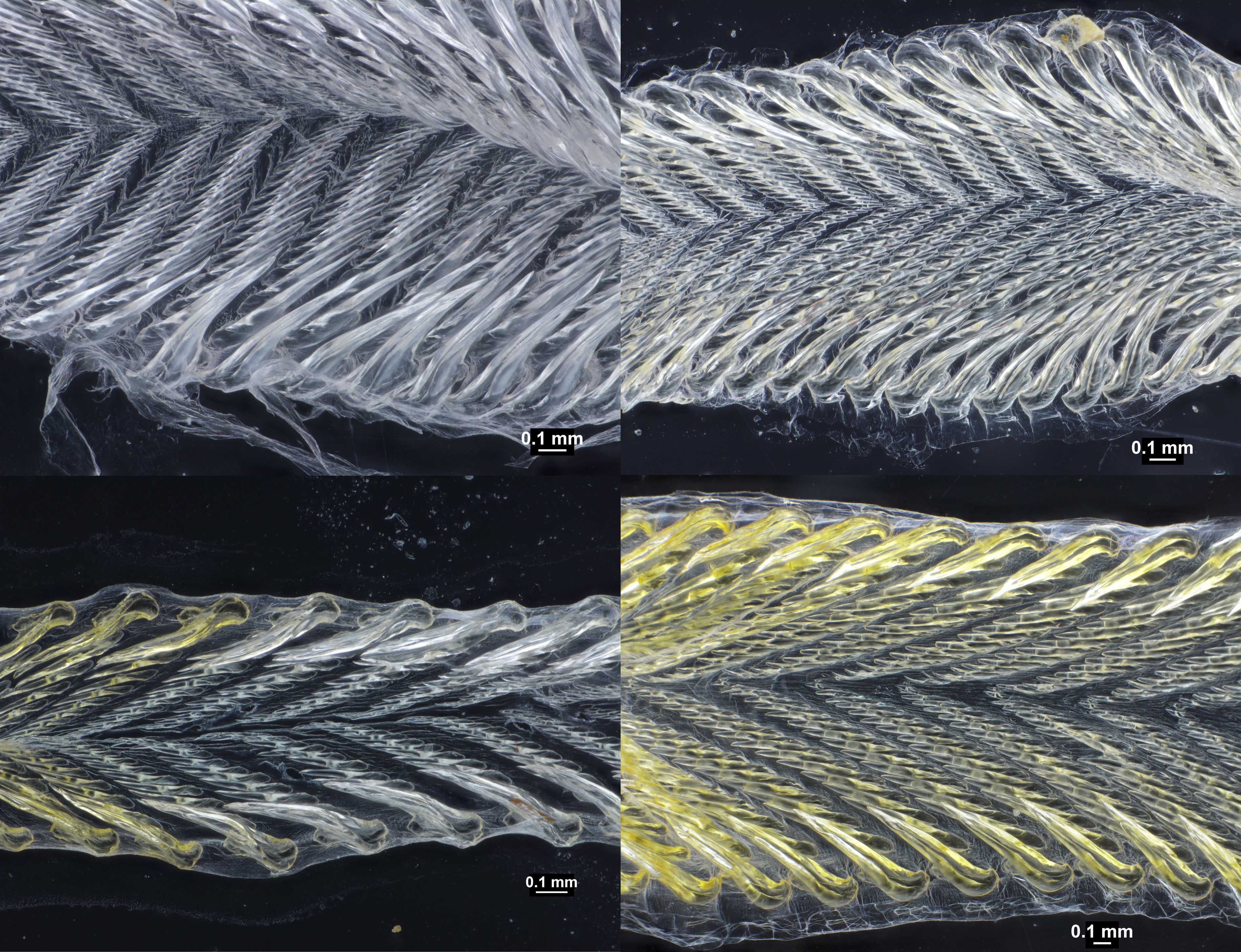

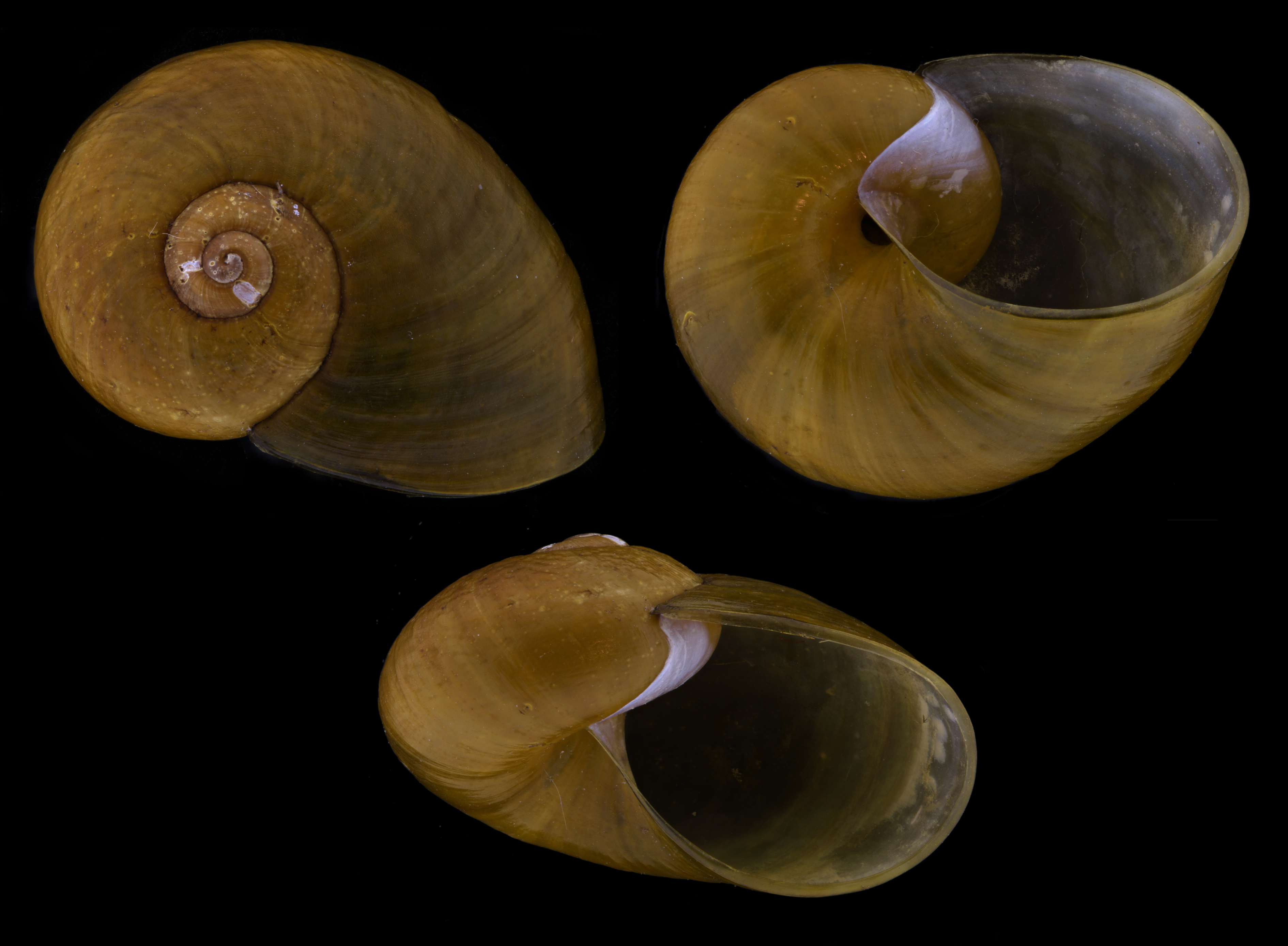

Snail researchers, or malacologists, often use the character of radulae to help distinguish between species. Both the shape, the number and the orientation of the radulae differ between genera and species. Dr Fred Brook, a New Zealand malacologist, has used Canterbury Museum’s microscope camera to photograph the radulae of several unnamed snail species. Below are high resolution images of radulae from different species. Each image, which shows an area only a couple of millimetres wide, contains multiple rows of tightly packed radulae. Despite their distinctive teeth, snails are still more easily and commonly identified by their characteristic coiling shells.

With such fearsome teeth, these snails are clearly a danger to New Zealand's earthworms, but they are now in danger themselves. They are threatened by species that humans have introduced to Aotearoa New Zealand. Rats, possums and hedgehogs eat them, while deer, goats and pigs change their habitat, which makes it harder for them to avoid native predators like the weka.

This decline can be tracked using the Museum's scientific collection of snail specimens, which includes valuable historic material. This collection has expanded recently thanks to Canterbury Museum Research Associate Dr Ian Payton. He is donating to the Museum his important collection of snail specimens, along with that of his late colleague and friend John Marston.

Ian worked for the Forest Research Institute and later Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research from 1975 to 2013. This meant he visited many remote locations around Aotearoa New Zealand and built an impressive collection of land snails, which includes many undescribed species. One particularly fine specimen was found at the side of the road in South Westland in 2010. The pristine shell, pictured above, is an undescribed species from an undescribed genus.

Specimens like this can help researchers understand our beautiful snail populations before it is too late. Unless we shift the balance between predator and prey in favour of snails, these beautiful examples of our indigenous biodiversity will continue their decline towards extinction.