The first feeling that strikes everyone on coming to New Zealand is its intense want of animal life. Mountains, plains, rivers, – mere features without a soul; for you can hardly dignify the miserable ground lark, the wailing weka, or the ghoul-like eel with such a title.

And with that wretched introduction, Mark Pringle Stoddart of Diamond Harbour went on to voice his support for the establishment of the Canterbury Acclimatisation Society in a letter to the editor of The Lyttelton Times. That was in February 1864. Two months later the Society was formed with the aim of improving the dull and lifeless environment that they found themselves in. To achieve this they went on to import and release a wide range of "innocuous animals, birds, fishes, insects and vegetables whether useful or ornamental". The roll call of founding members included Julius von Haast, the Museum’s first Director in the role of co Vice-president.

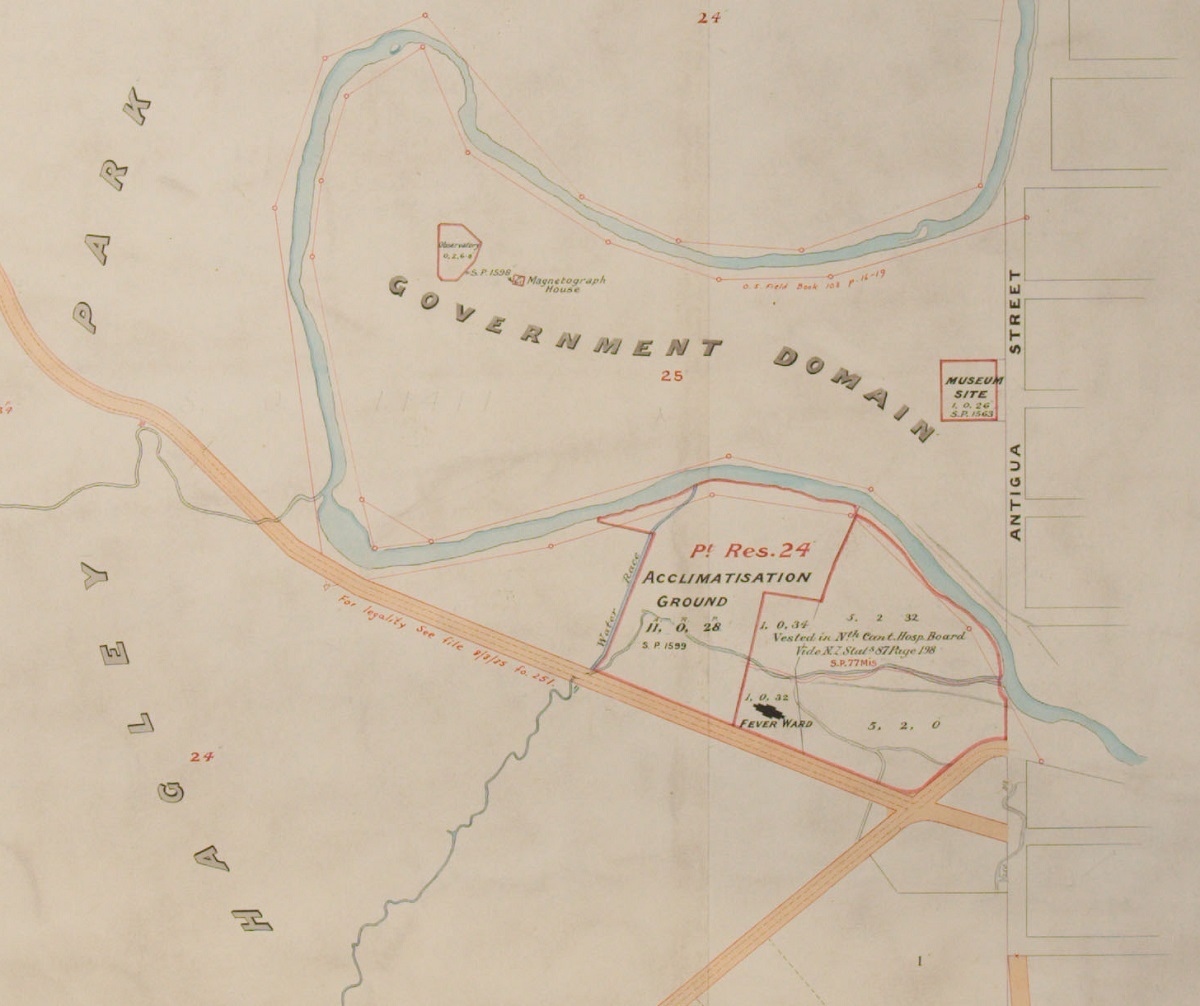

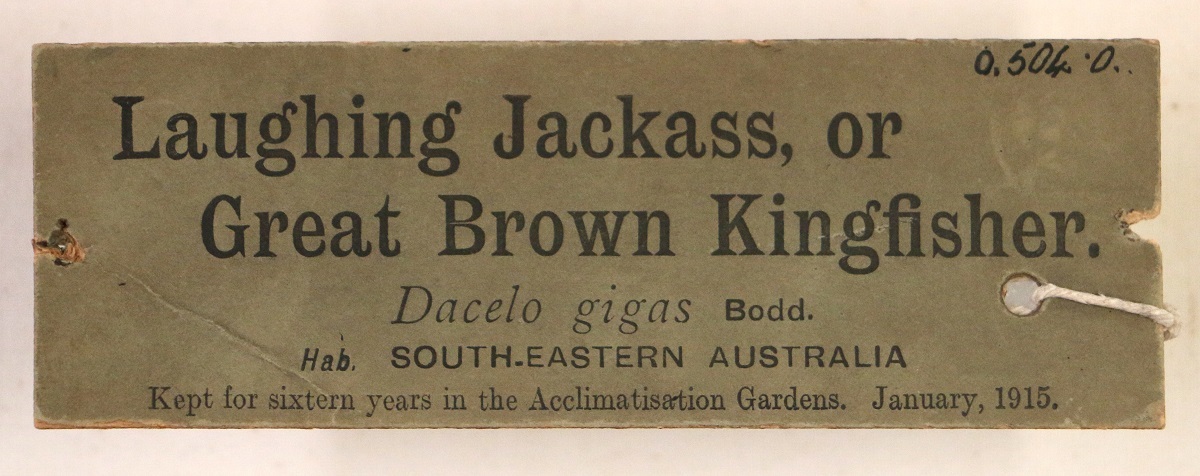

One of the first requirements was a plot of land to house the animals. The Canterbury Provincial Government quickly stepped in with 1.6 hectares of Domain land alongside the hospital between the Avon River and Riccarton Avenue. As Mark Stoddart had hoped, the society was then able “to convert a portion of the rather howling-looking common of Hagley Park” into a series of aviaries, animal enclosures, fish ponds and plant nurseries. This quickly became a de facto zoo for the citizens of Christchurch where exotic animals such as deer, kangaroos, emus, grey squirrels and even a Californian bear could be easily seen. It also became the source of some of Canterbury Museum’s collection such as the Kookaburra (below), and the New Zealand Scaup ducklings that can be seen in the Bird Hall.

However it was their dogged determination to populate the region with “proper” animals that became the Society’s lasting legacy. Rabbits, hares and many small bird species were released into the natural environment. They also had the honour of being the first group to import hedgehogs into the country, releasing them in the 1870s to control garden pests.

Having something decent to hunt and fish was also a high priority which led to the rearing of millions of trout in ponds in the Garden along with the release of deer and game birds into the countryside. Inevitably many of these species quickly flourished to become pests and the only response of the day was to release further predator species in the hope that they would eliminate the problem. When it came to the introduction of mustelids (ferrets, stoats and weasels) to control rabbits though, the Society were actually against it. But only because they worried it would decimate the introduced game bird population!

The Society continued operating out of the plot next door to the Museum until 1922 when the hospital needed extra land for a new nurses’ home. This prompted a move out to Greenpark near Lake Ellesmere where a new fish hatchery was established. In 1990 acclimatisation societies became incorporated into Fish and Game New Zealand, continuing to manage freshwater sport fishing and game bird hunting.

Unfortunately the historical actions of acclimatisation societies around New Zealand continue to have damaging repercussions for the natural environment. Many of the species introduced were anything but innocuous and share responsibility for the extinction of many of our native species. The “miserable ground lark, the wailing weka and the ghoul-like eel” have had to contend with some fairly disruptive neighbours since acclimatisation was set in motion 150 years ago.