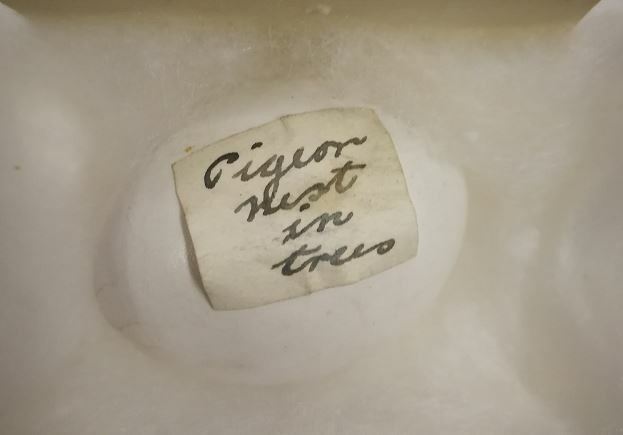

Every now and then we find something in the collection that no one knew we had. During the egg collection inventory and rehousing we found that we have two eggs of the extinct Passenger Pigeon.

In the nineteenth century Passenger Pigeons, Ectopistes migratorius, were the most abundant bird in North America and quite possibly the world. Witnesses described how during migration they took hours to pass over a single spot, darkening the sky and making normal conversation inaudible.

Nesting birds took over whole forests, forming what the famous ornithologist John James Audubon in 1831 called “solid masses as large as hogs-heads”. Observers reported trees crammed with dozens of nests apiece, collectively weighing so much that branches would snap off and trunks would topple.

The birds weren’t just noisy. They were tasty, too, and their arrival guaranteed an abundance of free protein. The flocks were so thick that hunting was easy – even waving a pole at the low-flying birds would kill some.

Harvesting for subsistence didn’t threaten the species’ survival, however. After the American Civil War came two technological developments that set in motion the pigeon’s extinction: the national expansions of the telegraph and the railroad. They enabled a commercial pigeon industry to blossom, fuelled by professional sportsmen who could use telegraphs to communicate quickly about new nesting events and follow the flocks around the continent. The new railroads allowed the hunters to ship huge quantities of shot pigeons to other areas.

Ultimately, the pigeons’ survival strategy – flying in huge predator-proof flocks – proved their undoing.

Environmentalism arrived too late to prevent the Passenger Pigeon’s demise, but the two phenomena share a historical connection as the extinction of the bird was part of the motivation for the birth of modern twentieth century conservation.

The last known Passenger Pigeon lived in Washington Zoo and was called Martha. Martha was named in honour of America’s first lady, Martha Washington. During Martha (the bird)’s lifetime, her caretakers offered a $1,000 reward to anyone who could capture a mate for her. No one ever succeeded and she died alone in 1914. After her death, Martha’s body was immediately packed in an enormous block of ice and sent to the Smithsonian in Washington, DC to be mounted.

Canterbury Museum received our two Passenger Pigeon eggs from Museum benefactors Benjamin Moorhouse and Edgar Stead. They in turn probably received them in exchange for endangered or extinct New Zealand birds.

Hardly anyone collected the Passenger Pigeon for museums as they were considered too common, and by 1937 passenger pigeon eggs were selling for US$300. Today they can sell for as much as US$50,000.