The trade in ancestral remains was common around the world from the eighteenth century to the early decades of the twentieth century. Many found their way into museum collections due a belief the remains would add to scientific knowledge about people of the past. Since the 1990s, the New Zealand Government, with the support of Māori and Moriori, has resourced the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, in repatriating Māori and Morirori ancestral remains back to New Zealand from around the world.

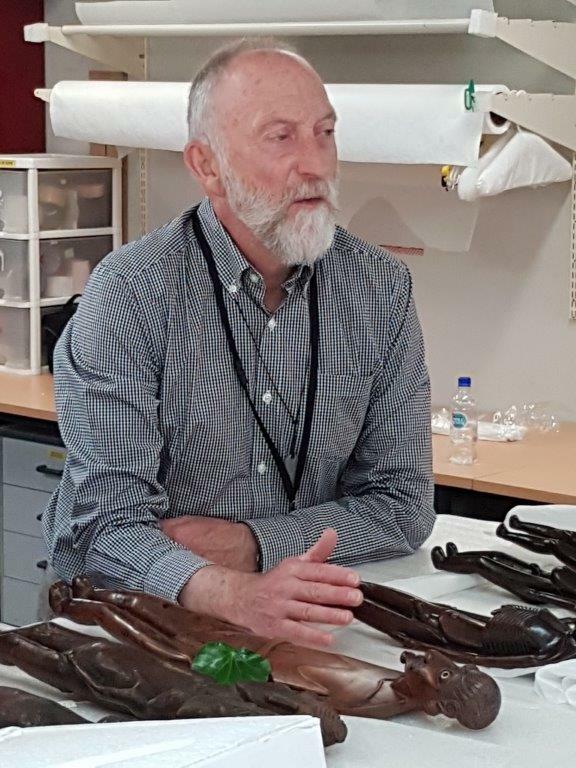

Last month a tipuna (ancestor) that had been in the care of Canterbury Museum for almost 70 years made the final 11,000 km journey home to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Together with a tipuna in the care of Otago Museum this was the first ever repatriation to Rapa Nui and only the first out of Te Waipounamu (South Island). Recently-retired Senior Curator Human History Roger Fyfe sheds light on how Canterbury Museum came to care for the Rapa Nui tipuna.

Well-known New Zealand author, E H McCormick, once described the passion that drives some people to collect things, whether they be books, bottles, stamps or butterflies, as the “fascinating folly”. We all collect things that take our fancy, but some people really get bitten by the bug. The particular preoccupation of British collector William Ockleford Oldman was ethnographic artefacts. During his lifetime he amassed one of the largest and finest private collections in the world.

It started in the 1890s when Oldman, a dealer in ‘native curiosities’ became increasingly fascinated by the beauty and workmanship of some of this stock. Before long, as his passion grew, he began to keep as many artefacts as he sold. As his interest developed so too did his eye for the finest objects and before long his modest two-storey house at 43 Poynders Road, Clapham, London, resembled a museum more than a family home.

Visitors to the house mentioned that the ground floor was where the Polynesian objects were kept and that upstairs were the treasures from Asia and Africa; elsewhere in the house were items from Melanesia, North and South America and Australia. Half of the ground floor was occupied by the billiard room and every part of the billiard room was occupied with treasures from New Zealand. A magnificent canoe prow took pride of place in the centre of the billiard table.

Amongst this collection were 22 (check) treasures from Rapa Nui. Carved wooden weapons, humanistic and animal-based carvings, dance paddles, sculptures and the Rapa Nui tipuna. Oldman, however, never ventured to places as distant as Rapa Nui. Nearly everything he acquired came from Britain, mostly from sales held at old estates and country houses of the wealthy. He had purchased the Rapa Nui tipuna from Sotheby’s auction house on 16 February 1939. (It was formerly from the collection of a well-know architect Senor Carlos Cruz Eyzaguirre of Santiago, Chile and may have previously belonged to his father, Carlos Cruz Montt.)

England at this time was also full of retired colonial administrators each with ‘native mementos’ from particular parts of the Empire: bronzes from Benares, weapons from Fiji, wooden figures from Nigeria, boomerangs from Australia and feather boxes from New Zealand. In time a great many of these things came under the auctioneer’s hammer and into the hands of private collectors.

What Mrs Oldman thought of the transformation of her home is not recorded. However, it seems likely that most guests and friends were like-minded scholars and enthusiasts, who felt quite at home amongst the glass cabinets and walls lined with curios. It would have been of little concern to them that a game of snooker after dinner was impossible when a guided tour was in the offering.

Throughout the Blitz in World War Two, the Oldmans refused to vacate their house, opting instead to take refuge in the basement along with their most precious items. The empty houses on either side were hit by incendiaries and burnt out. Oldman’s too, would have suffered the same fate had they not been on hand to extinguish every fire that started. Luck also played its part in their survival, a near miss left an impressive crater in their lawn.

As the years passed, the Oldman collection had increasingly attracted the attention of the academic fraternity. In the mid-1930s the Polynesian Society, with its nucleus of New Zealand scholars, encouraged Oldman to publish comprehensive pictorial catalogues of his Oceanic collections so that others could have access to these important treasures.