Canterbury Museum was recently gifted precious family items related to Lance Corporal George Fairbairn’s service on the Western Front in World War One.

These items reveal some of the emotional interactions that shaped wartime lives and resonated across several generations.

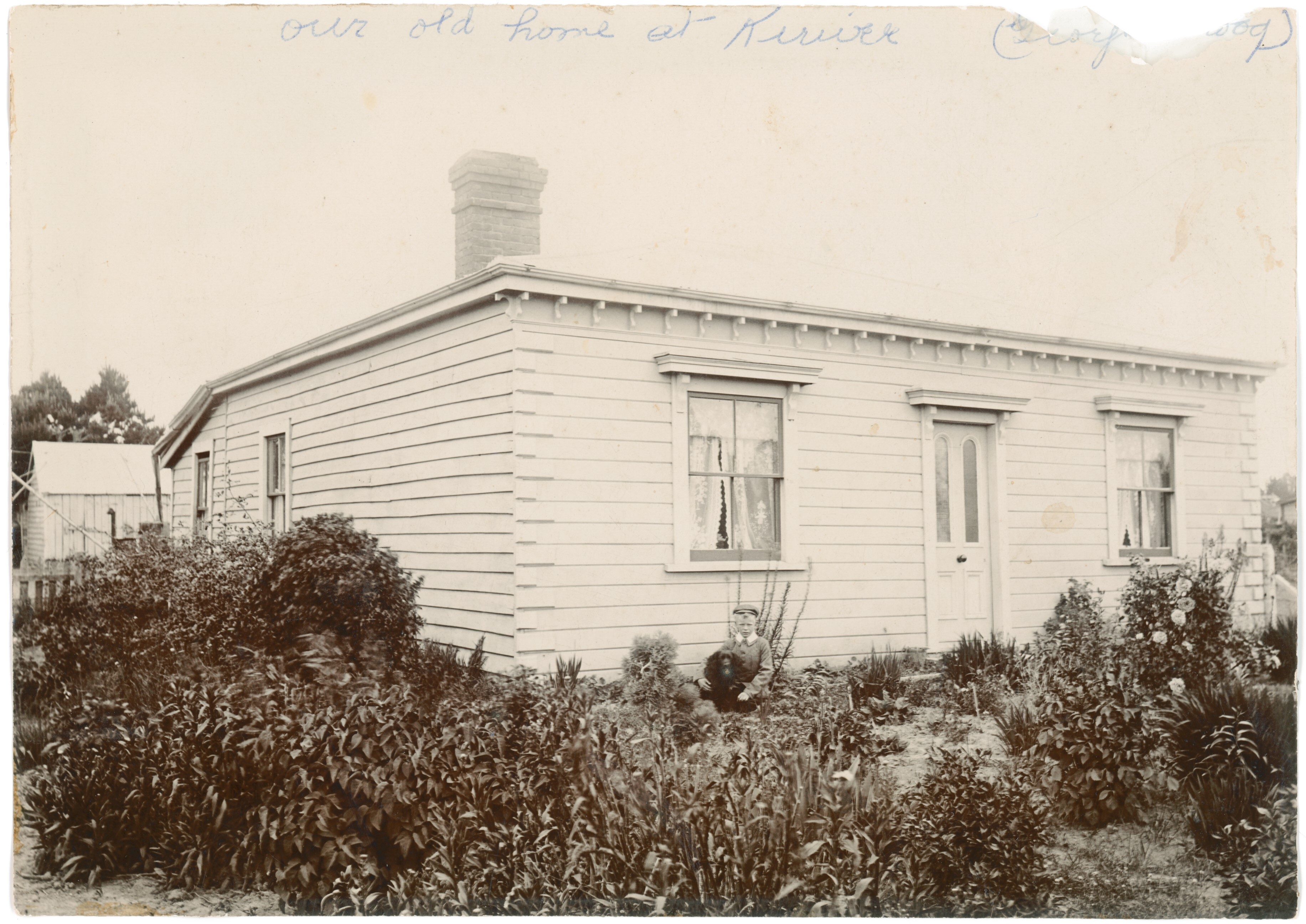

George Fairbairn was born in Kirwee, Canterbury in 1897 and served on the Western Front in the 14th Reinforcements, Otago Infantry Battalion between 1916 and 1917. He was wounded at the Battle of Messines. During that time, George sent embroidered postcards and an embroidered handkerchief from France to family and friends at home in New Zealand, including his sister Maud in Christchurch.

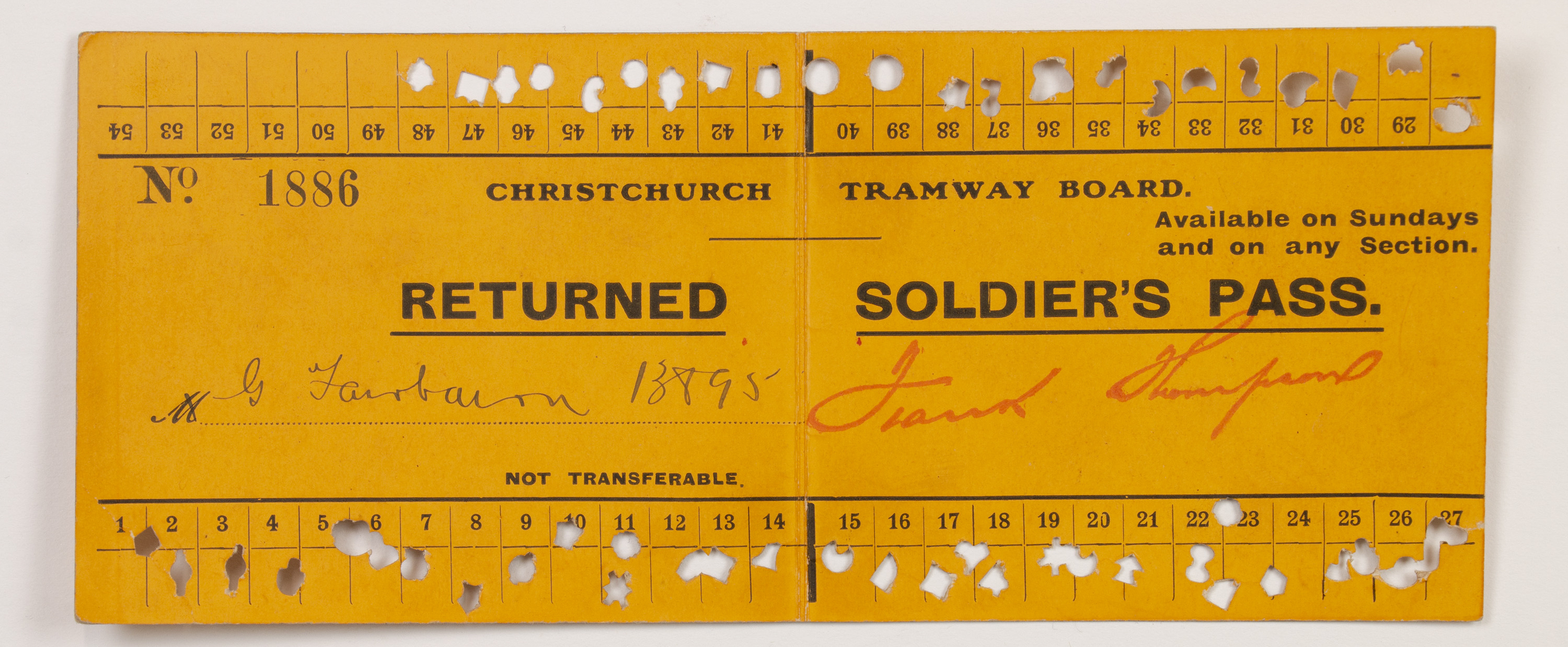

These precious items have stayed in the Fairbairn family ever since. The four postcards and one handkerchief were donated to Canterbury Museum in 2022 by Fairbairn’s son (who is also named George), alongside photographs and items from George’s return to New Zealand.

Although first made in 1900, embroidered silk postcards peaked in popularity during World War One with Allied soldiers in France. They sent them home as souvenirs to friends and family, often largely left blank and accompanied by letters.

The postcards were generally made of card and featured an embossed frame or border with embroidered designs on silk gauze panels. Sometimes the panel included a silk pocket, which could also contain a card or other souvenir.

The designs on the postcards varied and included patriotic flags, regimental badges and romantic floral patterns.

Accounts of their production methods differ, with some sources saying that the designs were probably hand-embroidered by people at home and completed in factories and others that their production was a completely machine-based operation.

These embroidered postcards are in museum collections around the world, but we are particularly interested in George Fairbairn’s postcards as they form part of Canterbury’s World War One story.

They show the relationships that George maintained during the War and how they were treasured by people at home for generations.

A similar souvenir item was the embroidered silk handkerchief. This handkerchief, still in excellent condition, was clearly well looked after by George’s sister, Maud, who had it for about 40 years. The embroidery reads “Remembrance from France.”

The handkerchief eventually made its way back to her brother George’s family. George’s son remembers they “were always in a special box with other trinkets which were known to me as unique items because of their embroidery skill and history.”

George also sent a postcard to Maud, in which he thanked her for the tin of cake that she sent him. George wrote: “It was bon I tell you”, clearly incorporating some French into his vocabulary. George wrote that he hoped everyone at home was well, but that he was "not to [sic] grand".

The other three postcards were addressed to Em, Emily and Emm, probably Emily Cameron McLean, who George married in Dunedin in 1919. Although only one postcard is clearly signed, From George, all three were probably sent by George.

Censorship laws at the time, which controlled what could and could not be communicated about the war effort, meant that family and friends at home often did not know the difficulties of life on the front. Yet the postcard pictured below contains rather frank language about trench warfare, in a down-to-earth tone:

"We go into the trenches again tomorrow dear, so I thought I had better drop You [sic] a line before going there, as it is hard to say what will happen there. We have had plenty of rain lately, which made things very miserable while it lasted. This place puts You [sic] in mind of Burnside after a few day’s [sic] rain. The mud is about the same in the trenches. It is over Your Knees [sic] at present. So we will have a very enjoyable time on this occasion."

Censorship aside, it could be difficult for those on the front to convey what was happening or how they were feeling. Postcards and letters were an important way to remain in contact with family and friends but writing them was not without its challenges.

George worked for the New Zealand Railways when he returned, retiring in 1953 as Comptroller of Stores. He lived in Petone for many years and was on the committee that installed the school dental clinic at Petone Central School. These clinics were introduced in New Zealand in the 1920s following concern about children’s poor dental health.

Sadly, his first wife Emily passed away in 1934 and their son Robert died from injuries in Egypt while serving with the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces in 1942. Following his experiences during the War, George was a member of the National Reserve during World War Two and was called up for service in New Zealand for almost 2 years.

During this time he was promoted to Corporal and then Sergeant. He married Nellie Colgate Smith in 1937 and they had two children together, one of whom donated these items to Canterbury Museum.

The postcards and handkerchief are beautifully made items that tell intimate and emotional family stories of the War.

Although the postcards only reveal snippets of George’s war experiences, they highlight his desire to maintain relationships at home and they have been treasured family objects for over 100 years.

This is part one of a two-part series. To read how one of the postcards became part of the Canterbury Museum collection, read part two.

For more information

For more about Canterbury and World War One , see the Museum’s online exhibition, Canterbury and World War One: Lives Lost, Lives Changed.