What do you call a fly with no wings? A walk.

Aotearoa is renowned for its flightless birds, with the kiwi probably our most famous animal. But evolving away from flight is not only restricted to birds. In fact, it is far more common in insects.

Ironically, some species of fly have given up their wings entirely, perhaps adopting the new name "walk" in the process. But why give up flying? Although it might seem counterintuitive, there are several evolutionary reasons for wing loss being an advantage to these species. Flies have shed their wings to adopt a disguise, live more easily among fur and feathers, and avoid getting blown away by high winds.

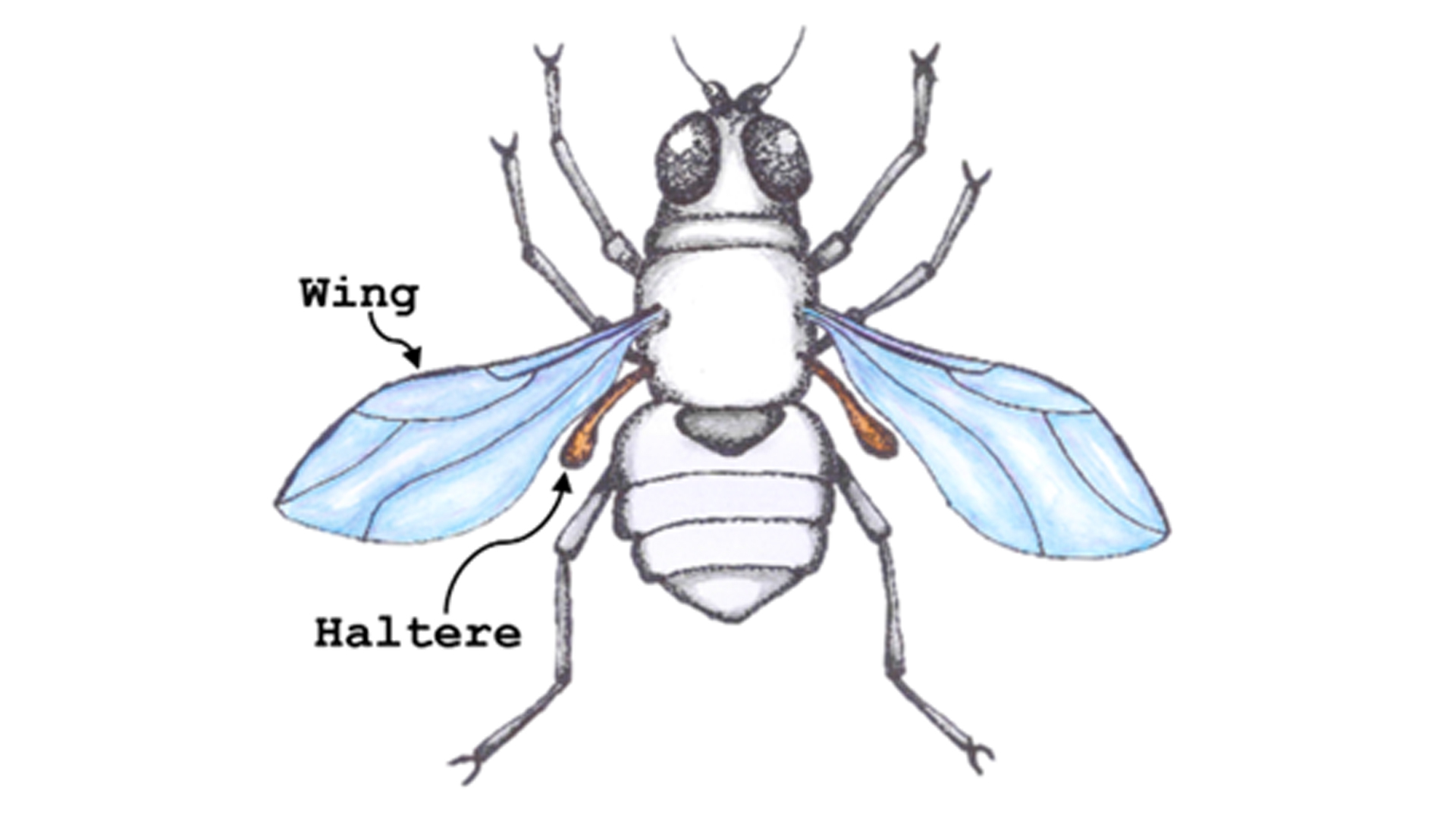

The name Diptera literally means two-winged. This is a defining trait that separates flies from other insect groups like Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) and Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps). Instead of having four wings (a pair on each side) like a butterfly or bee, flies have just two wings, and their hind wing is reduced to something called a haltere which looks like a tiny drumstick sitting just behind their forewings (see diagram below).

Some fly species have a parasitic relationship with ants or termites and secretly live inside their colonies. To blend in with their hosts, the adult female flies either develop without wings or shed their wings before entering a nest. In this instance, being wingless is an advantage, allowing the fly to move around inside the nest without being recognised as an imposter. They are then able to lay their eggs in the nest. The larvae later hatch and feed on the ant pupae.

Some wingless flies pick on animals much larger than themselves. The Hippoboscidae, or louse fly family, are parasites on birds and mammals. Their louse-like appearance comes from their flattened body shape, which makes them difficult to squash and is well-suited to moving amongst feathers or fur.

Another major reason for wing reduction or loss is living in environmental conditions which make flight both risky and energetically costly. An excellent example of this kind of environment is the Subantarctic Islands, where conditions are often extremely cold and windy. Close to three quarters of the insect fauna are flightless. In this case, flying requires more energy, which is better dedicated to other activities. There is the added risk that in high winds a fly could be blown away. In fact, recent research has determined that the more severe and frequently windy conditions in the Subantarctic Islands is the main reason for the disproportionately high number of wingless insects, including flies, found there.

In the Museum collection, we have several examples of these flies collected from the Subantarctic Islands. There are two flightless species in the kelp fly family (Coelopidae). Baeopterus robustus has significantly reduced wings, while Icaridion nasutum has wings reduced to tiny strips and lacks halteres entirely.

Kelp flies, as their name suggests, live on kelp and seaweed that washes up along the coast (technically known as wrack). This is a tough and exposed habitat and flies are frequently overwhelmed by extreme weather conditions, waves and ocean surges. Here, wings are not always useful, especially when you spend much of your time moving around inside clumps of kelp and seaweed rather than needing to cover large distances. The species name of Baeopterus robustus alludes to their hardiness when it comes to surviving and thriving in this habitat and the genus name Baeopterus is descriptive of their small wings.

Entomologist Charles George Lamb examined and described numerous Diptera collected from the Subantarctic Islands in the early nineteenth century. One species he named nasutum, which translates from Latin as "big or long nose". This is most likely a direct reference to Lamb’s description of the species having a prominent labrum (one of the mouthparts) which can have a nose-like look in some flies.

More poetically, Lamb gave one fly species the name Icaridion nasutum after Icarus from ancient Greek mythology.

Icarus took to the sky on wings made from feathers stuck to his arms with beeswax. But he flew too close to the sun and the beeswax melted. Poor Icarus lost his wings and fell from the sky.