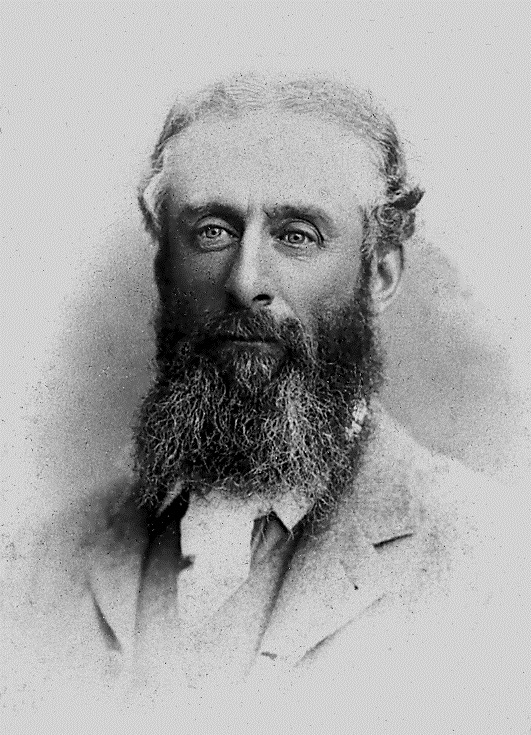

Although little-known to New Zealand art history, John Henry Menzies (1839–1919) was a prolific carver and designer active during the New Zealand Arts and Crafts period. His work shows a deep interest in Māori art which he combined in varying degrees with botanical reliefs, Celtic patterns and text. Quite what triggered his interest in design, carving and Māori art is not known, but his period of artistic activity lasted from around 1880 to 1910 while he lived and farmed on Banks Peninsula.

Although English born, Menzies’ work addressed the question of nationalism current in New Zealand society at the time. Indeed it was still a live subject in 1931 when the artist Christopher Perkins wrote in Art in New Zealand:

Whoever invents and imposes on New Zealand a rational, typical, loveable and indigenous domestic architecture will be a national hero…. Two natural starting points… are provided by the Maori house with its noble porch in simple continuation of the main roof, and the cubic unit of ferro-concrete, quake proof and permanent.1

Perkins seemed unaware that decades earlier, Menzies had been experimenting in exactly this area.

In 1894, Menzies began building the house Rehutai at Menzies Bay which he designed around a large central hallway built to capture the spirit of a whare whakairo or Māori meeting house. The hallway was decorated with painted kōwhaiwhai patterns, text relating Māori proverbs in te reo, and Māori carving.

Rooms leading off the hallway were decorated with carving, some with botanical reliefs featuring plants associated with Scottish, Irish and English nationalism. Others featured carved Māori patterns and figures.

Menzies’ carved furniture also functioned as decoration to interior spaces showing he (consciously or sub-consciously) understood and responded to the strong link between Māori art and Māori architecture. One design theme shared by several pieces was to incorporate a model whare whakairo (carved meeting house) or pātaka (storehouse) to perform the role of a cupboard or case.

Overall, around 80 pieces of Menzies’ carved furniture survive. Most (but not all) are carved with Māori designs and/or indigenous plants. Gifted to children and grandchildren they brought the indigenous into the everyday lives of Pākehā homes that otherwise followed European design trends.

From 1905 to 1906, Menzies tackled another ambitious building project, the Little Akaloa church, St Luke's. In the interests of its longevity he constructed St Lukes from concrete and lined the interior with Oamaru stone. Menzies built St Luke's on a traditional cruciform floor-plan rather than a design that responded to the whare karakia or Māori church model (such as the famous church at Ōtaki). He nevertheless incorporated traditional Māori architectural decoration in the form of kōwhaiwhai on the church’s exposed rafters and designed the stained glass windows in response to tukutuku lattice-work panels that decorate Māori buildings.

The baptismal font, pulpit, altar and altar rail were made from white Mt Somers stone and carved elaborately with a combination of botanical reliefs and Māori and Celtic patterns. Biblical quotes are also carved into these pieces. In St Luke's, Menzies brought Māori art together with a range of other motifs to give a distinctively New Zealand identity to Christian worship.

Menzies’ study of Māori art relied on visits to Canterbury Museum, which at that time displayed its collection of taonga in the whare whakairo Hau te Ana Nui o Tongaroa, carved and painted by Hone Taahu and Tamati Ngakaho (Ngati Porou). He also studied photographs and visited other museums on his travels.

Menzies’ final major work was to paint the patterns he had collected from his years of research into 28 studies. These were published in 1910 as a lithograph set, by Christchurch firm Smith and Anthony. Entitled Māori Patterns Painted and Carved, this was Menzies’ best known work nationally.

Menzies had a vision of incorporating Māori art into everyday life. His designs translated Māori art from the traditional objects he studied to new forms, giving an indigenous identity to everyday things. Because of the isolation of his buildings, and because the majority of his furniture remains owned privately by his descendants, Menzies has not received the national attention he deserves. Had his work been better known in 1931, Christopher Perkins may well have dubbed Menzies with the title ‘national hero’.