One of the most well-known taonga in Canterbury Museum is this small wooden carved figure of a kurī or Polynesian dog found at Moncks Cave near Redcliffs. It's on display in our gallery Iwi Tawhito – Whenua Hou.

Made of kānuka, this is the only known carving of a pre-European dog and an extraordinarily rare example of a wooden ornament (it was possibly a pendant).

Kurī arrived in New Zealand with the East Polynesian ancestors of Māori about 700 years ago. Of the Polynesian domesticated animal species, dog, pig and chicken, only the dog was successfully introduced here. Kiore (Polynesian rats, Rattus exulans) arrived at the same time but these may not have been deliberate introductions.

Several traditional stories including those associated with exploration and the great migration feature kurī. In one, a dog on scenting land jumps overboard and the waka (canoe) follows it to shore. In another, a dog is sacrificed to appease the gods and to obtain favourable winds. Kupe is said to have brought kurī with him when he discovered Aotearoa (New Zealand). According to the story, he left one waiting so long in Hokianga, Northland that it turned to stone.

The guardian deity of kurī is Irawaru, the brother-in-law of Māui. Angered at Irawaru’s laziness, Māui pulled his spine, nose and ears into the shape of a dog. When Māui’s wives asked him about their brother he told them to call "Moi" (the call for a kurī).

Kurī were small with short legs, having a long muzzle like a terrier with a notably strong jaw and pricked ears. They tended to be white, black or a combination of colours. Their tails are said to have curled upwards, a feature that is evident in the wooden figurine. A distinctive trait of the kurī apparently was that it didn’t bark but rather howled.

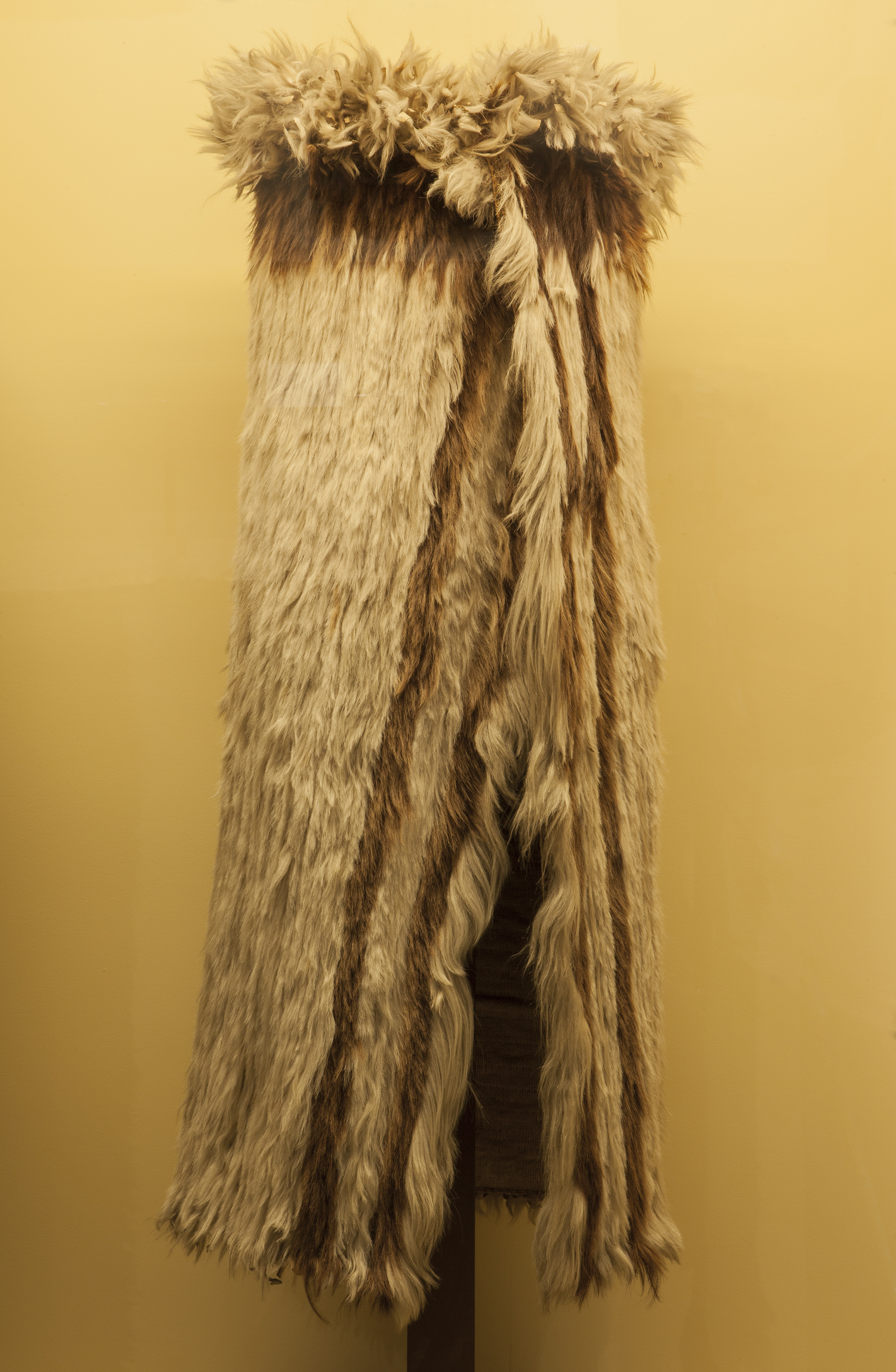

Dog bones and teeth are found in the earliest archaeological sites across the country. These dogs were a food source and their bones and teeth were used for industrial purposes, including making fishhooks and personal ornaments such as dog tooth pendants. Their pelts were used for clothing like kahu kurī (dog skin cloaks) or to decorate weapons. Figures of kurī are also represented in rock art at several sites in Canterbury and North Otago.

The archaeological record provides us with useful information about what role kurī played after their deaths. Identifying their role during life is more difficult, but they would have had several roles as watch dogs, hunting dogs and companions. The occasional deliberate burial of a kurī has been found, suggesting that it may have been a treasured pet or companion, but such finds are not common. Early European accounts provide some further clues. George Forster, for instance, who was the naturalist on board the HMS Resolution during Cook’s second voyage to the Pacific in the early 1770s, reported seeing kurī on waka in Queen Charlotte Sound. He recorded:

A good many dogs were observed in their canoes, which they seemed very fond of and kept tied with a string round their middle... The food which these dogs receive is fish, or the same which their masters live on, who afterwards eat their flesh and employ the fur in various ornaments and dresses.

Missionary William Colenso left some detailed accounts of the role of kurī in parts of Māori society during the early nineteenth century. He suggests that the population may no longer have been large and that many of them were given names and were highly prized. They were frequently used for hunting ground-dwelling birds such as weka and kiwi. Colenso also suggests white-haired kurī were particularly prized, especially if they had long-haired tails. The tails of these kurī were shaved and the hair used for ornamental purposes. By the nineteenth century dog meat had become a tapu dish and was given to tohunga (chosen expert or priest) presiding over certain ceremonies such as the tattooing of a chief.

Kurī were effectively extinct by the mid-late nineteenth century largely as a result of interbreeding with European-introduced dogs.