A series of prints created about 250 years ago by a samurai artist depict everyday life and beauty in Japan.

Canterbury Museum has cared for the prints since they were generously donated in 1969 as part of a wonderful bequest from Mrs Frances May Bailey.

Pillar prints, a form of ukiyo-e, were originally produced in large numbers in Japan from the mid-1700s. They are woodblock prints in a long, thin format, printed to specific measurements and intended to decorate the interior pillar posts of Japanese households, or be hung in alcoves. The exposed prints were expected to wear out - a low-cost substitute for highly regarded painted hanging scrolls - and would have been replaced by another print being stuck over the top. Some were also converted into hanging scrolls.

Due to their age and temporary nature, they are now very rare. All four of the Canterbury Museum prints are by the artist Isoda Koryūsai (1735–1790) who was the most prolific producer of pillar prints, creating at least 450 in his lifetime. Koryūsai was initially employed as a samurai - a Japanese warrior caste - by the Tsuchiya family. But then he became a rōnin, meaning he was a samurai without a master, and moved to Edo (now called Tokyo) where he started working as an artist. It is thought that he studied woodblock art under Suzuki Harunobu (1724–1770), in part due to the heavy influence seen in his work. Schools and masters passed down techniques and styles generationally.

Harunobu was a renowned innovator, the first to produce full multicolour (nishiki-e) prints in 1765. This technique involved using multiple separate wood blocks to create a single image. Harunobu was considered a master of the popular art form ukiyo-e, woodblock prints depicting “the floating world” of everyday life and beauty in Japan. The prints were purchased by all members of society, eventually gaining recognition and distribution around the world.

Koryūsai was creating pillar prints in the 1770–80s, in the middle of the period of ukiyo-e production, during the Edo (Tokugawa) period (1615–1868).

The pillar print has been called the most unique innovation within ukiyo-e, due to its very narrow width. It was the narrowest of the Edo period prints. This posed an exciting compositional challenge to ukiyo-e artists. Printing the artworks was also a challenge. Two woodblocks are joined together lengthwise to create the pillar print. The join of the boards would have been filed down, so that it was invisible on the print. The join can still be seen in some prints, but not in our four pillar prints.

The narrow format also brought new opportunities to artfully use the negative space in the picture frame. In pillar prints, the complete picture is suggested without being seen. The edges of the image are usually sliced off, as if you are viewing the scene through a slit or gap. It is like you are quietly spying without anyone noticing.

Koryūsai also had a considerable output outside of pillar prints, leaving over 2,500 designs; his subjects included courtesans, actors, samurai, the natural world and subjects from history or literature.

In the above pillar print (hashira-e), a young girl plays hane-tsuki - a game that resembles modern badminton. She wears a long grey kimono decorated with snow-covered bamboo leaves and stylised birds. The length of her kimono sleeves indicate that she is young, and the inclusion of snow in the pattern is appropriately related to the title of the print: Mutsuki

(The First Month). It is from the series Furyu juni ki (Fashionable 12 Months). Snow is common in Japan during the winter month of January.

The colours have faded considerably since the print was produced, which is very common for pillar prints. It is difficult to find pillar prints that have not been exposed to the elements and faded or altered in colour during their 250-year (or so) lifetime. The upper part of this print would have originally contained mica – a luminescent powder added to the colour that creates a shiny effect.

This pillar print (hashira-e) features a beautiful courtesan on parade with her child attendant (kamuro). In the image she is pictured underneath a house lantern at night. Her obi belt is decorated with fat rabbits. The courtesan’s name is Utagawa and she is from Matsubaya House in the red-light Yoshiwara district of Edo. This ukiyo-e is from the ‘Shin Yoshiwara Edo-chō’ series.

In this pillar print (hashira-e) the artist Koryūsai shows an action scene, where a young man is helping a young woman to board a boat. Her foot can be seen resting on the gunwale as she steps from the land, her hand grasped in his.

The depiction suggests they are lovers, with her knee, leg and foot exposed. Her black geta sandal lies carelessly on the bank. The base of her kimono is decorated with beautiful daffodil flowers and leaves.

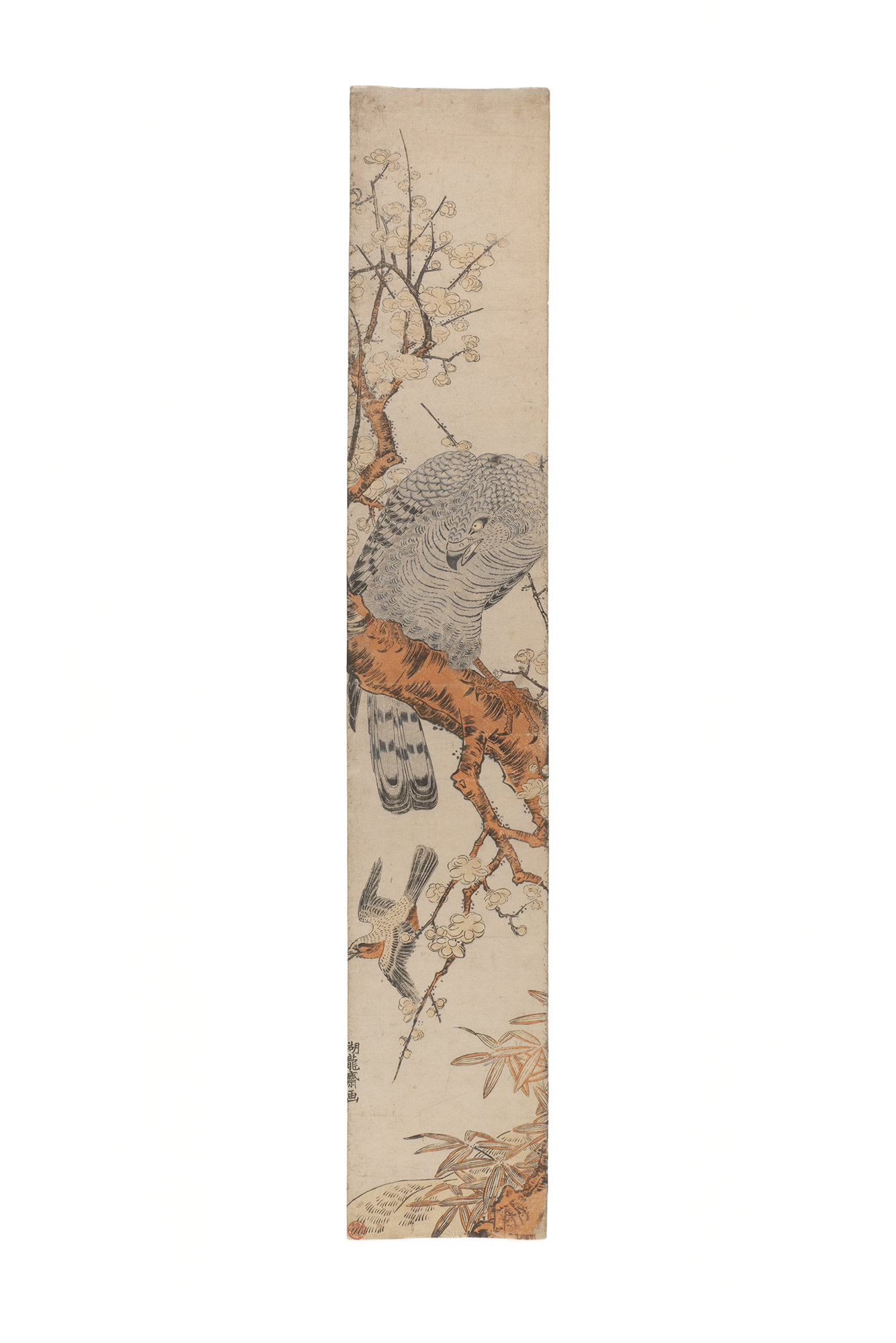

This pillar print (hashira-e) draws heavily from Chinese painting conventions, in both composition and subject. It depicts a hawk perched on a plum tree, eyeing up the bird flying below.

Together these four pillar prints are beautiful examples of Japanese art and offer a fascinating insight into life in eighteenth century Japan.