On 7 January 1839, the daguerreotype process was announced to the members of the French Académie of Sciences in Paris and photography was born. News of its discovery spread like wildfire across the globe.

Before 1839, the only way to record an image was to draw or paint it. The ability to capture a photographic image revolutionised life in countless ways. It is hard to imagine a world without photography.

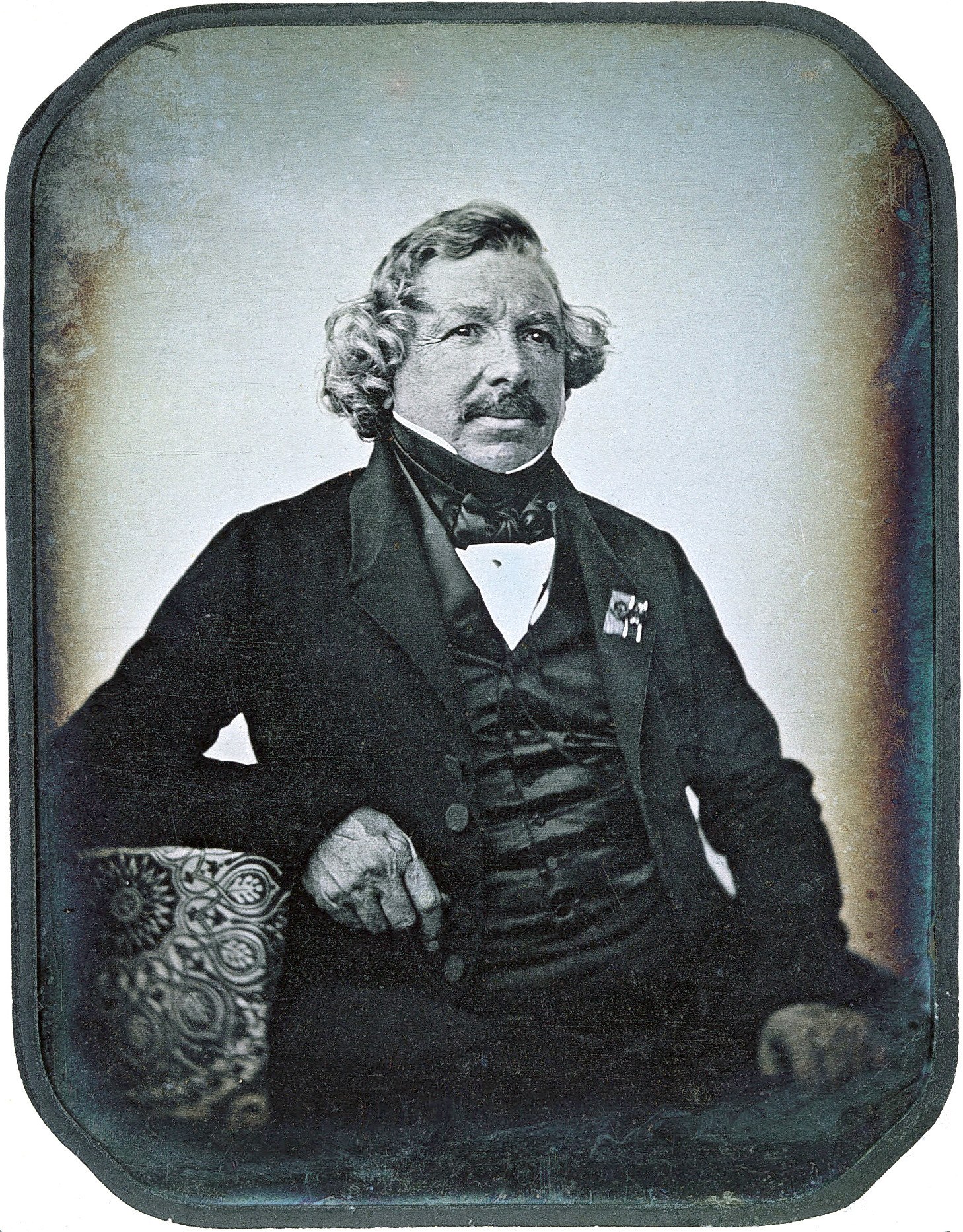

Louis Daguerre, after whom the daguerreotype is named, had experimented with the idea of fixing an image onto a surface for several years before revealing his process. He was not alone. During the 1820s, Nicéphore Niépce had also been working on a way to produce a permanent image and in 1826 or 1827, he successfully, although crudely, captured a view of the rooftops of the town of Le Gras. In 1829, he and Daguerre formed a partnership which ended with Niépce’s death in 1833. At the same time in England, Henry Fox Talbot was also experimenting with photography and on 25 January 1839, just over a fortnight after Daguerre’s announcement in Paris, Talbot disclosed his process to the British Academy.

The daguerreotype process fixed an image onto a sensitised, silver-plated sheet of copper. Prone to damage, the fragile surface was covered with a layer of glass and housed in a decorative case. Daguerreotypes are often confused with ambrotypes, a later type of cased photographic image but the difference is easy to spot; daguerreotypes have a mirror-like surface while ambrotypes are not reflective.

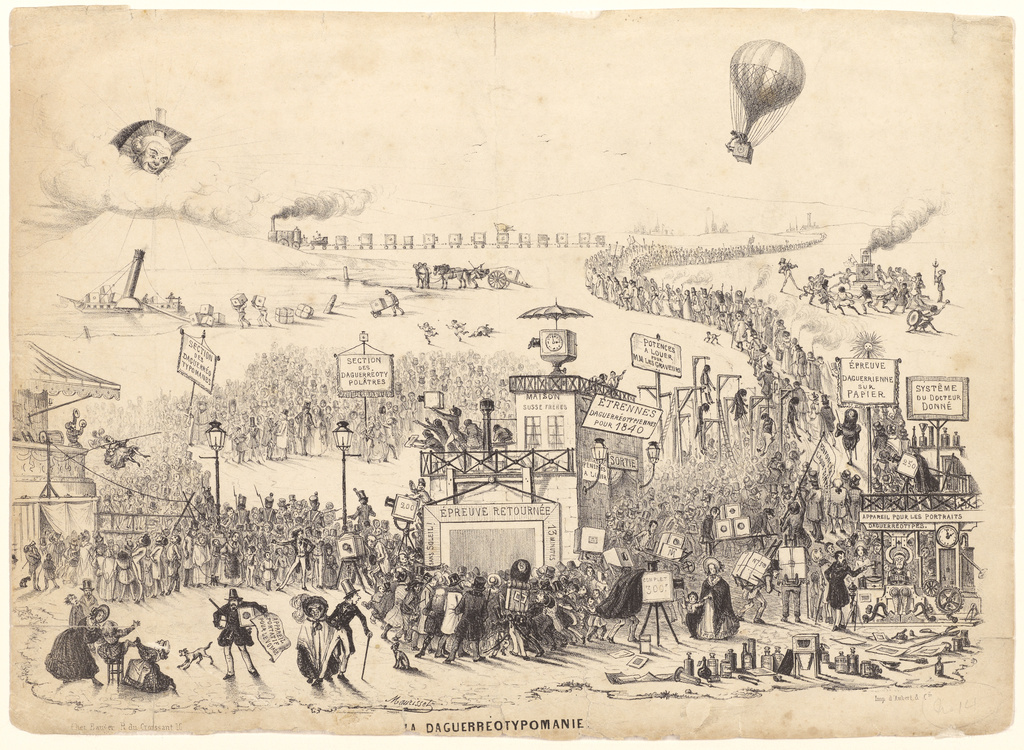

The clarity and lustrous appearance of daguerreotypes and their novelty proved popular with the public. Soon Daguerreotypomania – the desire to have one’s daguerreotype taken – gripped France. A humorous French cartoon from December 1839 shows the pandemonium as hordes of people line up to have their portrait taken.

Daguerre relinquished his patent for the daguerreotype to the government of France and in exchange received a lifetime pension. The French government, in turn, gifted the invention to the world, with the exception of England and Wales. An arrangement could not be made with the British government to pay Daguerre and as a result, the process was protected there.

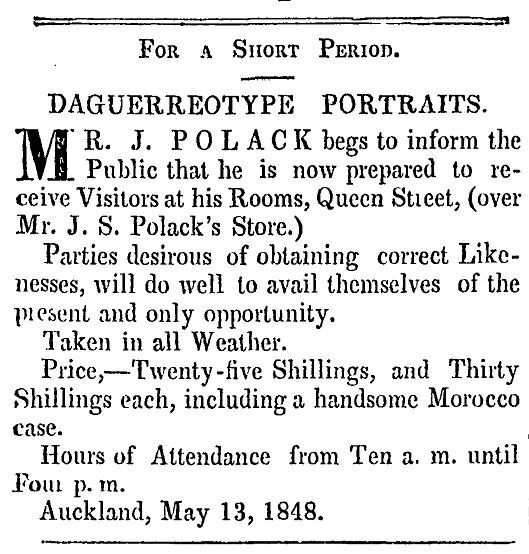

Through newspapers and arriving immigrants, daguerreotypes were known about in the Colony of New Zealand. However, it wasn’t until May 1848, nearly 10 years after daguerreotypes were introduced in France, that the first daguerreotype artist arrived in Auckland. Isaac Polack advertised in the The New Zealander newspaper that he was prepared to take "correct likenesses" at his Queen Street premises. Residents of Canterbury had to wait even longer. On 9 May 1857, the Lyttelton Times excitedly reported that photography had broken out like an epidemic in the province: "Quite unknown in the place a year ago, we have now a professional artist well known in the northern provinces, and another on the point of coming; two students practising the art; and, we believe, one amateur."

Although thousands were taken, known New Zealand daguerreotypes are rare, mainly because they were not marked with the studio’s name. Only a handful have been attributed to New Zealand photographers and a few more are known to be images of New Zealanders by unidentified studios. There are no known Canterbury daguerreotypes, although Canterbury Museum’s collection holds a photograph thought to be a copy of a local-made one. In an album she compiled in 1869, Mary Annie Hargreaves added a photograph of herself and her parents taken in Lyttelton in 1857. The photograph is a carte-de-visite, a small photograph mounted onto a cardboard backing and a format that was not available in Canterbury until the early 1860s. On the back of the photograph, Mary has noted that it was copied from a daguerreotype. It is possible that the original daguerreotype was taken by John Nicol Crombie who established a temporary studio in Lyttelton in 1857. Mary’s copy of a daguerreotype is not unusual. Too large and bulky to fit into an album, daguerreotypes were often copied into a format such as a carte de visite that could be easily fitted.

With advances in photographic technology and the ability to produce images on paper, daguerreotypes fell out of favour, and by 1860, most New Zealand photographers had stopped taking them.