When he established Canterbury Museum in 1867, Museum founder Julius Haast made it his mission to bring the many wonders of the world to Christchurch.

To achieve this, he made use of a resource that he had a plentiful supply of: moa bones. Haast exchanged moa bones for other treasures with overseas museums, who were keen to get their hands on the skeletons of New Zealand's lost avian giants. He also sold the bones to raise money to buy specimens and other objects for Canterbury Museum.

One of Haast's first purchases was the salted skin of an Asian elephant from Sir William Henry Flower of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

For three years this specimen was on display in the Museum simply as a skin nailed to the wall. However, in 1877 the expert Austrian taxidermist Andreas Reischek travelled to New Zealand to help set up displays at the Museum. One of his first tasks was to turn this skin into a realistic taxidermy mount of an elephant. This was no simple task.

The Lyttelton Times of 14 November 1877 described the process:

An elephant of immense size is now being proceeded with, the preparatory work including the erection of a massive framework of iron, to which intermediate portions of wood are attached. Upon this frame-work the animal has to be modelled, the finer portions being executed in clay, and over all the prepared skin has to be fitted. The wetted skin of this elephant, in the state of which it has to be placed over the model, weighs upwards of 1200 lbs [540 kg], and a series of pulleys have been arranged for hoisting it onto the artificial carcass.

The mounted elephant went on display in 1878 to great acclaim.

It wasn't the first elephant displayed in a New Zealand museum, nor the first elephant seen by the New Zealand public. In 1868 a carnival owner imported a live elephant. This individual was exhibited first in Dunedin before being walked to Christchurch. On the way it consumed the highly poisonous tutu plant and died near Duntroon in North Otago. The skeleton was sold to the Colonial Museum in Wellington (now Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa).

The place where the elephant died was named Elephant Hill but is now called Elephant Rocks. Many people believe that the area was named after the elephant-like limestone formations seen nearby, never imagining that a real elephant briefly lived and then died there.

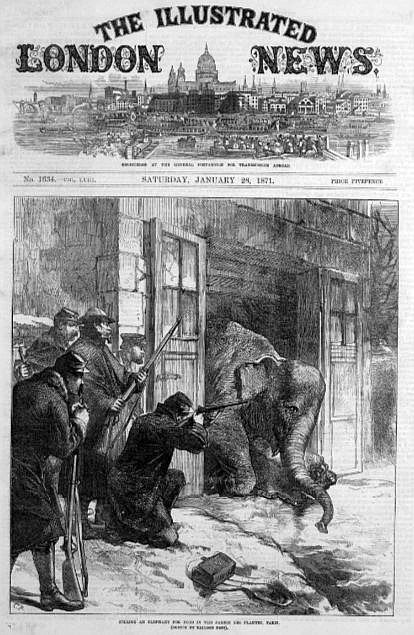

By the 1930s, a curious rumour was circulating about Canterbury Museum's elephant. An article in The Press on 17 September 1935 stated that the elephant was one of two from the zoo in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris, that were killed and eaten by the starving citizens during the 1870–71 siege of the city.

Unlikely as it sounds, the eating of these elephants and other zoo animals actually happened. Castor and Pollux, the elephants, appeared on Christmas menus in 1870.

However, it's extremely unlikely the Museum's elephant is either Castor or Pollux. Not only is it stretching credibility to suggest that the starving people of Paris undertook the time-consuming and complex task of removing and preserving an elephant's skin, but there are contemporary reports of people using the untanned elephant skin to repair their shoes.

The Museum's elephant has suffered greatly from the ravages of time. It has been in storage since the early 1980s. In the late 1980s, a family of possums got into its storeroom through a hole in the roof and tore a hole in the elephant's straw-filled stomach to make their nest.

The elephant's storeroom has been modified since it was put in there, and it's now impossible to get it out without removing the roof or floor.

The February 2011 earthquake nearly destroyed the elephant, but its frame has been reinforced and it is now awaiting restoration. Hopefully it will return to display in a redeveloped Canterbury Museum!