My previous work in spider identification has mostly involved large samples of introduced spiders from urban areas and farmland. Although all spiders are brilliant, beautiful creatures to study under the microscope, I found myself gazing wistfully at the neglected pages of my spider family guide: the strange, enigmatic treasures, unique to New Zealand, which would be at home in any sci-fi or fantasy film.

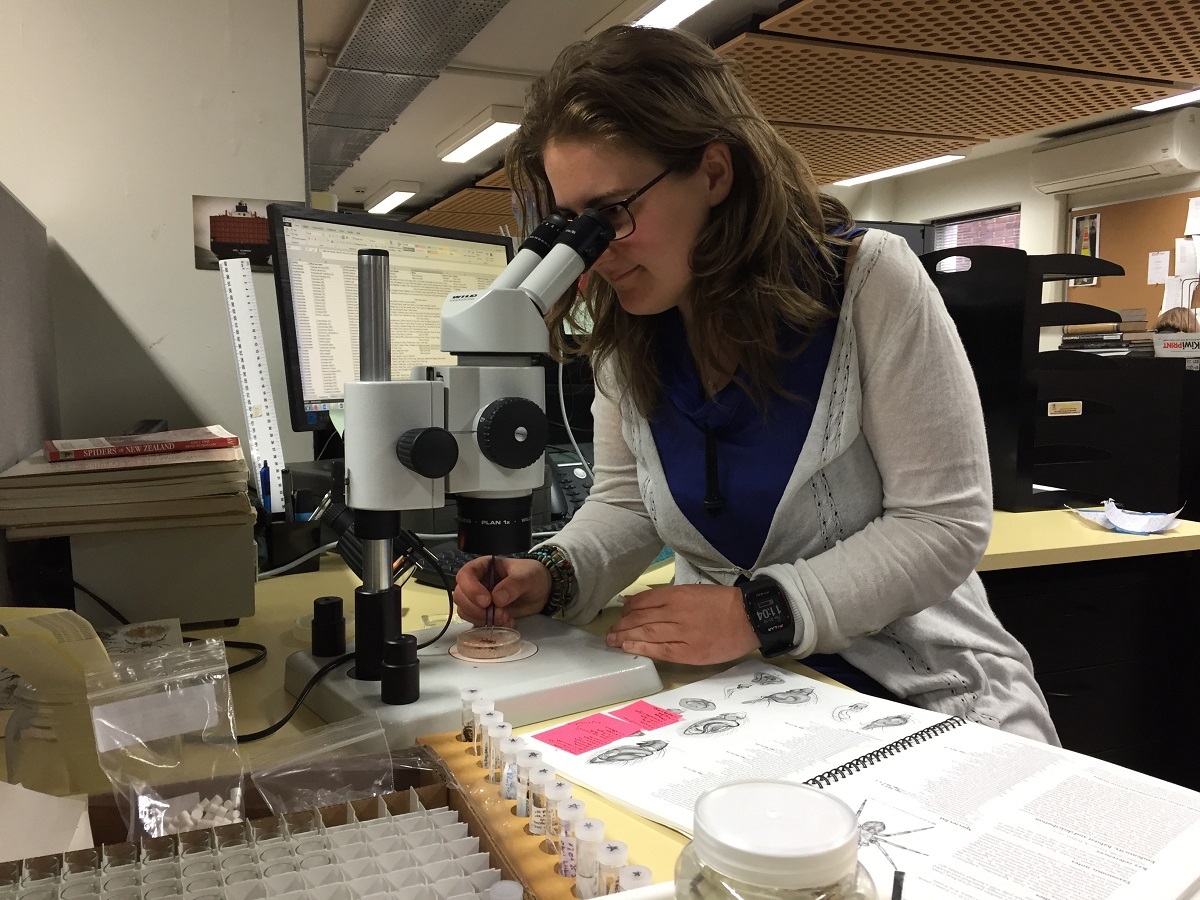

My new post as Associate Curator has opened up a world of spider families to explore. For the last month, I have been cataloguing Canterbury Museum’s amazing collection of 1,830 spiders. The collection aims to represent New Zealand spider fauna, focusing on Canterbury. Fifty of the world’s 112 spider families are represented in the collection, 39 of which have native representatives in New Zealand. Many species in the collection are only found in New Zealand.

A particular asset to the Museum’s collection is the 222 specimens representing the family Orsolobidae. Orsolobid spiders are tiny (less than 3 mm), have only six eyes (most spiders have eight), and live in soil and leaf litter. While some orsolobid species are found in Africa, Australia and South America, New Zealand has by far the most species. Very little is known about orsolobids in general; their behaviour and the roles they play in our native ecosystems remain mysterious.

Another tiny spider struck me as odd when I was looking at samples from Divide Creek in Fiordland. Most spiders in the sample were juveniles, which usually lack features to help identify their species, and are thus useless to science. But one individual with a disproportionately large head region and long, impressive chelicerae (fangs) stood out. I flipped through the spider guide, knowing that this spider must be from one of the more unusual families. Finally, I turned the page to reveal an illustration of the spider I had been looking at: it was in the family Mecysmaucheniidae (pronounced MEK-iss-MAOK-en-ear-day), also known as trap-jaw spiders.

Mecysmaucheniids are bizarre beasts. They are, perplexingly, found only in southernmost South America and in New Zealand. New Zealand’s species are found here and nowhere else. Their incredible jaws are specially adapted for fast, powerful striking when the spider is hunting other spiders. When the spider prepares to strike, its jaws open at a 90° angle to its body. Specialised hairs stick out in front, ready to detect movement. New Zealand mecysmaucheniids have by far the fastest, most powerful jaws. When a hair is triggered, the jaws snap shut in 0.00012 seconds; over 800 times faster than you can blink.

Most of the spiders in the collection are less than 5 mm long, however, we have our fair share of large beauties. The heaviest spider in New Zealand is the tunnelweb (Porrhothele antipodiana), a reclusive but powerful spider found throughout New Zealand. A harmless relation of the infamous Sydney Funnelweb, the largest tunnelweb in the collection is 27 millimetres long. Male tunnelwebs are at risk of becoming meals unless they use specially evolved appendages to hold the female’s palps (modified legs) while mating. However, once he has the upper hand he may change his mind about love, and eat her instead. Spider romance leaves much to be desired.

New Zealand’s largest spider, boasting a 15 cm legspan, is Spelungula cavernicola, the Nelson cave spider. In the collection, we have two male specimens and an egg sac. A member of the Gradungulidae, or long-clawed spiders, Spelungula has elongated claws at the ends of its legs, which it uses to hook prey while hanging onto cave walls. Spelungula are extremely rare and heavily protected by law, so you would have to be lucky to see one in the wild.

My next task is to add to the collection by searching Canterbury for spiders that aren’t yet represented at the Museum. The specimens I find will be added to this gradually evolving encyclopaedia of New Zealand spiders, as a reference for researchers and any other interested parties. Great arachnologists of the past, including Ray Forster in the 1950s, have cared for the spider collection at Canterbury Museum. Identifying and cataloguing specimens collected by them is a reminder of the history and heritage our museum has represented for 150 years, and will continue to represent for the years to come.