If you were a European woman in Victorian New Zealand, there’s a chance your favourite pastime was to make scrapbooks or albums documenting the natural world.

This presumes, of course, that you had the spare time and means to pursue your passions (as opposed to women who were kept too busy with work, household chores and childcare duties). Amateur botany and naturalism were popular interests. The unique flora of Aotearoa New Zealand was sought after and compared with British specimens.

Sometimes these albums contain beautiful drawings and illustrations copied from published works.

I've recently been investigating an album full of gorgeous illustrations, which is part of the Museum’s pictorial collection. The album was recently uncovered during the Museum inventory of the collection, but its origins are a mystery. It has no identifying numbers that would record who the donor was, or when the album came into the Museum. The only clues are an inscription of the maker, Emily Stevens, and the date of 1 February 1856 handwritten inside the front cover.

The album contains carefully outlined and painted illustrations of British fungi and mushrooms, each identified by a handwritten species name at the bottom of the page. I have not been able to find out anything about the artist, Emily Stevens.

Seeing as the illustrations were of British fungi and not New Zealand species, I decided to see if I could find any connection between known British mycologists (fungi studiers) and Emily Stevens. This led me to published works from the 1800s, featuring illustrations of fungi. When I noticed that some of the illustrations in the book by Anna Maria Hussey were familiar, I realised that Emily Stevens’ fungi were copies of known works.

Further referencing (and a google reverse image scan or two) highlighted that they were largely copies from two publications: Anna Maria Hussey’s 1847 Illustrations of British Mycology and James Sowerby’s 1797—1803 Coloured Figures of English Fungi or Mushrooms.

Here are a couple of comparisons:

Female mycologists such as Anna Maria Hussey played a significant role in the study of fungi. In a predominately patriarchal Victorian society, women scientists usually had a working relationship with a male scientist, although not always, and often that involved the woman illustrating the specimens and sending them to their male counterpart for identification. Hussey worked closely with mycologist Reverend Miles Joseph Berkeley and the specimens of fungi that she and her sister, Frances Reed, sent to him are now in the mycological herbarium – which, brilliantly, is called the Fungarium - at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, London.

Emily Stevens also copied from James Sowerby’s Coloured Figures of English Fungi. Sowerby was initially an engraver and botanical artist who trained at the Royal Academy. He made 440 drawings of British fungi and 193 models. Twenty nine of these models survive in the collection of the Natural History Museum in London.

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū also holds an album full of beautiful Victorian watercolours. The maker of this album is again a mystery, but it dates from around the 1880s. Gallery curator Ken Hall and I have been looking into this album to try and identify the artist of these mainly local watercolours.

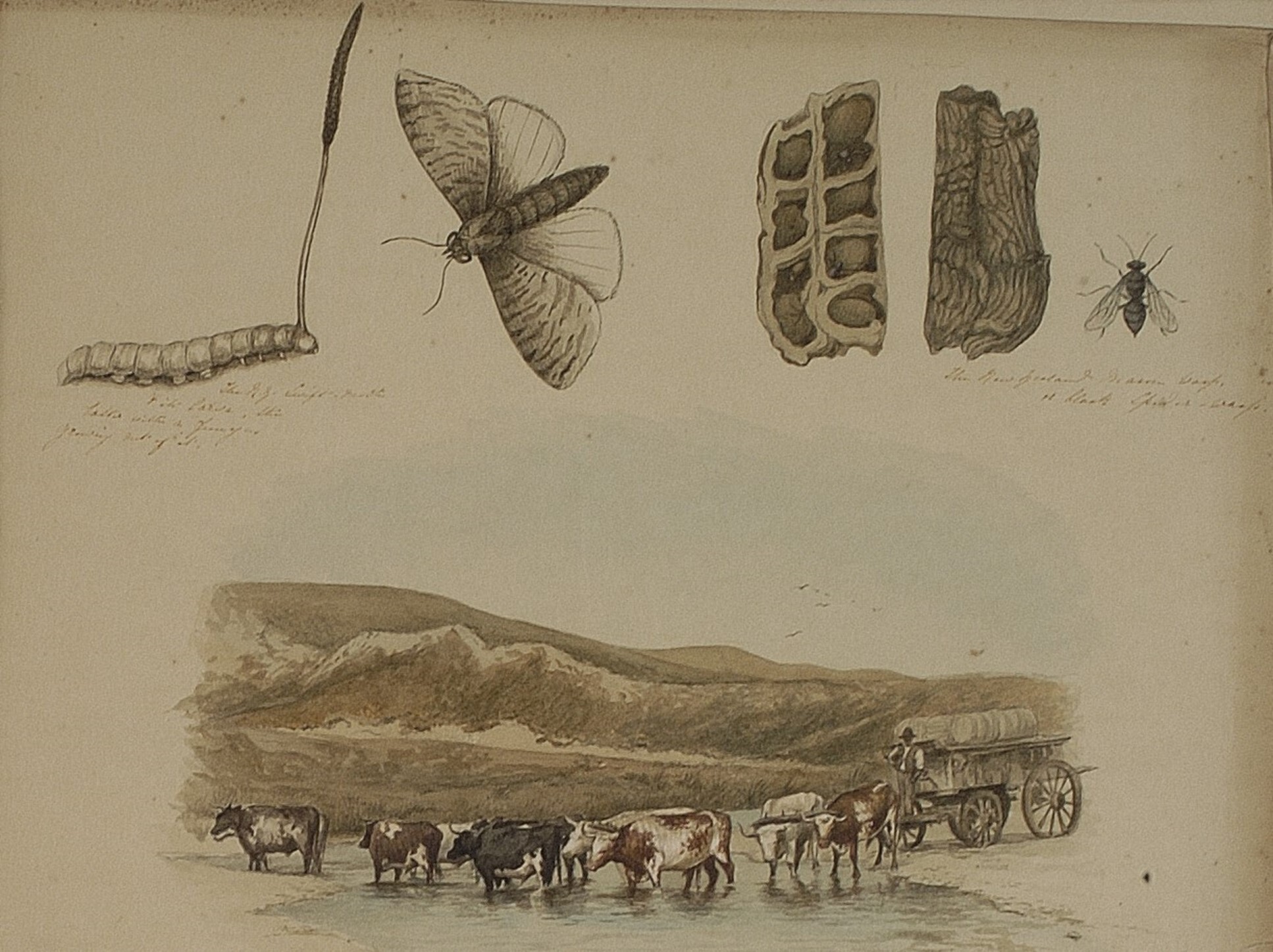

The album, which can be viewed online here, contains Aotearoa New Zealand and Waitaha Canterbury scenes, along with local botanical and animal studies, and illustrations of Tennyson’s narrative poem Idylls of the King. There are descriptive inscriptions on some of the illustrations and a mycology reference in this drawing of a parasitic Cordyceps fungus, known as the 'zombie' fungi, sprouting from a caterpillar (in the upper left corner below).

At one point we suspected we may have uncovered the identity of the mystery artist. I noticed a strong similarity between the album’s Ranunculus lyallii artwork and an original painting by well-known New Zealand botanical illustrator Georgina Burne Hetley (1832–1896).

As the works within the album are all executed so proficiently, it is reasonable to consider that someone with training produced the album.

The handwriting in the album is also very similar to Hetley’s with a comparable G and B. But within the album there is another copy, which practically rules out a Hetley attribution. The illustration of Hoheria populnea shows a branch very unlike Hetley’s version with drooping leaves. It is however a very close match to a Hoheria populnea illustration by Sarah Featon (1848–1927) which appears in her 1889 publication The Art Album of New Zealand Flora: being a systematic and popular description of the native flowering plants of New Zealand and the adjacent islands.

Closer looks at the individual illustrations then revealed that they are all likely copies of published works. The Christ Church Cathedral on the same page as Hoheria populnea looks to be from an 1888 photograph by Frank Arnold Coxhead. The Tennyson illustrations are after steel engravings by Gustave Doré.

It seems our mystery artist was another Victorian copycat.

Today, if you see something appealing, you can quickly photograph it with your phone. In Victorian times it was not so easy. Scrapbooks and albums such as these, were a way for women to record their interests and preserve the images they liked. They enabled the sharing of information with friends and family. They were a place for women to practise and hone their drawing techniques. Most of all, they encouraged science and discovery in the natural world, sending some naturalists on journeys across the world.

The specimens that mycologists like Anna Maria Hussey collected are still relevant to science today. The publications that she, Georgina Hetley and Sarah Featon produced put women at the forefront of science. They were obviously admired by their contemporaries such as Emily Stevens, who copied their work with vigour and skill.