The atrium of the redeveloped Canterbury Museum will be home to one of the largest skeletons in the world.

The Museum’s blue whale is one of our most precious taonga (treasures) and many visitors fondly remember it hanging in the Garden Court.

Although it has not been on display in nearly 30 years, the whale will take pride of place suspended from the atrium roof when the Museum reopens towards the end of 2028.

At almost 27 metres long, we think our whale is one of the largest skeletons – possibly even the largest skeleton – in any museum in the world.

How did such a magnificent specimen end up at Canterbury Museum?

In February 1908, the whale washed up, dead, on a beach near Ōkārito on Te Tai o Poutini, the South Island’s West Coast. The whale was female and about 80 years old. It probably died of old age at sea.

News reports of the event caught the eye of Museum Curator – a position equivalent to the Director today – Edgar Waite. Accompanied by Museum taxidermist William Sparkes, he travelled to Ōkārito to see the whale with a view to having its skeleton brought back to the Museum. Waite wrote of his first sight of the whale:

“Looking down the beach we saw what resembled a large vessel bottom upwards. This was the whale. No words of mine can convey the slightest idea of the enormous mass spread out before us.”

The whale had been on the beach for 2 weeks at this point, and Waite also described the smell:

“I cannot say at what distance the odour of the dead whale was apparent, but it was confidently predicted that both Mr Sparkes and myself would lose our breakfasts, as others had done, but we proved to be superior to such a trifle.”

The whale’s corpse had been claimed by locals Joseph Burrough and Norman Friend, but they were willing to sell. The difficulty would be extracting the skeleton and getting it back to Christchurch.

After a few attempts to cut away the flesh on the whale’s lower jaw, Waite and Sparkes accepted that they lacked the manpower or equipment for the job and returned to Christchurch.

Waite tried to organise another expedition to go over, properly equipped, to get the bones but was unsuccessful. Appearing to accept defeat, he wrote to Burrough and Friend to say that he now had “no interest” in the whale.

Luckily for the Museum, ornithologist (someone who studies birds) Edgar Stead was up for the job. He agreed to buy the whale off Burrough and Friend and organised a group to go and retrieve the skeleton.

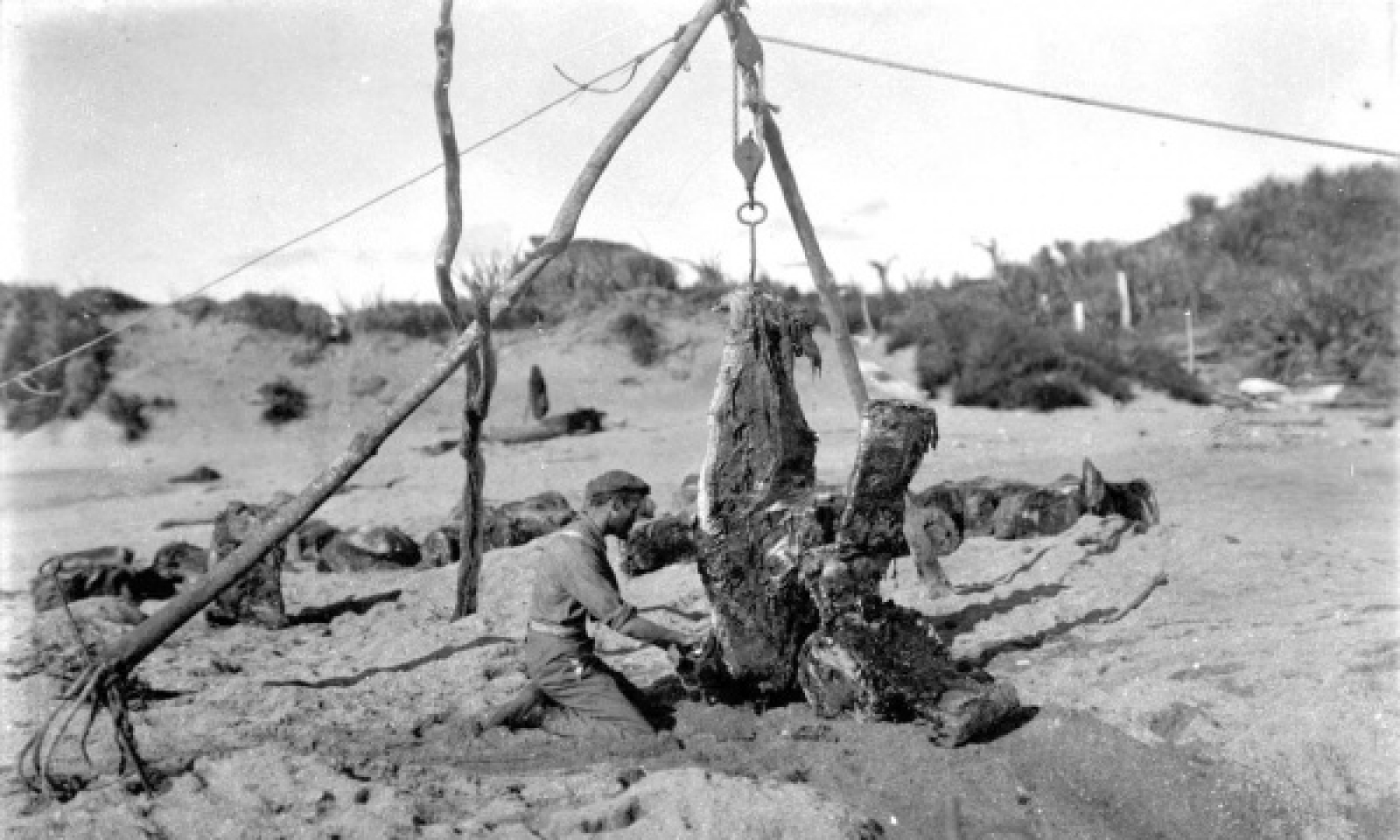

Stead and his three companions – brothers Colin and Cecil Walker and one J H Clayton – arrived on the Coast in late July 1908 armed with (according to an article Stead wrote about the expedition) “hay-knives, slashers, shovels, butcher’s knives, huge iron hooks, blocks and tackle, axe, saw, etc., and also a considerable supply of disinfectant”.

The whale had been lying on the beach for several months at this point and was not only rotten but partially buried in the sand. Stead described his arrival on the site as follows:

“[F]or the first time, we got a good whiff of the scent in which we were to work. The oil had oozed out through the skin, and solidified with the sand and shingle forming a bed of stuff not unlike concrete. This was so hard that, later on, in several places, we had to loosen it with a pick. And it smelt. How it smelt! It was as if forty thousand freezing and soap works were holding a reception, with sewerage systems for guests. I felt it was beyond my limit, and so, having found the tail was intact, I said we’d return to camp and get settled down a bit.”

Stead’s group spent the next month butchering the huge, rotting carcass of the whale, cutting out each enormous bone, scraping off the flesh and washing it in the lagoon. Heavier bones were lifted out using a makeshift pulley system. The workers lived in tents and a small cabin nearby and were nourished by a diet of bread, treacle and stewed swans which they shot on Ōkārito Lagoon. They were plagued by sandflies, particularly when working around the shady side of the whale carcass.

On 21 August, they were finished. After organising for the skeleton to be shipped to Lyttelton, Stead and his crew returned to Christchurch where he wrote to the Museum offering to sell the whale for £500.

“Seeing the size of the whale and the fact we have already received enquiries about the skeleton from America we do not think we are by any means over-estimating its value at £500,” he said.

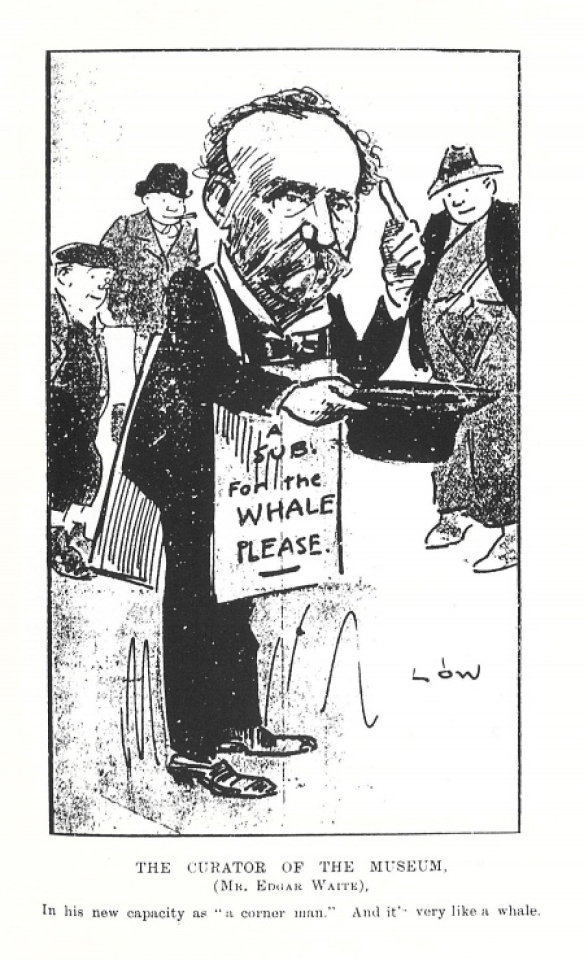

The Canterbury College Board of Governors – then responsible for overseeing the Museum as well as the future University of Canterbury – agreed to put £200 of its own funds towards purchasing the whale. Museum Director Waite was tasked with raising the rest through donations from the Canterbury public, with Stead and his whale-flensing companion Turnbull contributing £50 to get the effort started.

Waite was eventually successful in raising the money, and the whale skeleton came to the Museum via Greymouth, Wellington and Lyttelton. All the bones except the skull arrived on 15 October 1908, with the skull following in February the next year.

Waite and Museum staff got to work on assembling the skeleton and working out a way for it to be displayed. This involved building a special shelter behind the Museum building, the cost of which was met by a £400 grant from central government.

The whale display opened on 23 March 1909 and was an instant hit with the Canterbury public. It remained virtually unchanged until it was packed down in 1973 to make way for the construction of the Roger Duff Wing. It was covered in plastic and left to lie outside for 3 years before being rehung in the new Garden Court, under an overhang of the Antarctic Gallery.

By 1993 it was becoming clear that more than 80 years’ exposure to the open air was taking its toll on the whale skeleton. It needed to be conserved and displayed in a new area, but with the Garden Court being built over to form what is now the Museum’s Level 1 Temporary Exhibitions gallery, there was no suitable space for it to be displayed. The difficult decision was made to store it until a solution became available, and the whale was removed from display in 1994.

The creation of a space where the whale can be displayed in its full glory has always been one of the key goal’s of the Museum’s redevelopment project, which we have been working towards since 2001.

In the new Museum, we plan to hang the whale in the atrium. Just after coming through the doors you’ll see it, suspended from the ceiling high above you. You’ll walk beneath its skull, ribs and spine to access the galleries.

Finally, more than a century after it was found dead at Ōkārito and over 30 years after it came off display, the whale will be back.